Lyz Bly, Ph.D./DRB (She/They)

August 15, 2024

Above photo by the author

A little more than a year ago, my yard was national news.

You can call it a stretch to claim this, but it’s true. Cleveland Heights Mayor Khalil Seren’s declaration that May 2023 be “No Mow May” (NMM) got him and the city some serious PR; he was interviewed on CNN and the “radical” suggestion that it was ok to not mow was noteworthy enough for the AP to pick up the story, so it also showed up in a variety of local news outlets across the U.S.

The city’s part in NMM meant that grassy lots connected to buildings maintained by city workers would grow beyond the six-inch limit. Doing so would reduce the City of Cleveland Heights’ carbon emissions, and also and allow plants such as dandelion, burdock, and feverfew grow to support bees, butterflies, and birds. Moreover, the city’s lawn police would not respond to snippy neighbors’ calls and emails (with photos of the lengthy grass as “proof”) about fellow citizens’ grass. [1]

It seemed simple enough, and it was just one month: May 2023.

Unfortunately, in ten years of Cleveland Heights residency, I’ve found the simple act of cutting the grass, maintaining the lawn to be a dangerously controversial endeavor for those of us who can’t or choose not to conform to cookie-cutter lawns. Even more unnerving, I’ve come to understand the ways in which Seren’s identity, along with my own queer identity–were a part of the uproar over NNM.

The reality of suburban conformity around grass and sexual identity hit me one day while shopping for chicken scratch at the (now dead to me) Tractor Supply in Solon, just 15 minutes from my inner-ring suburb.

There, a 70-something blue-eyed white man was talking to another man, also apparently from my suburb, because I hear his voice raise to an uncomfortable pitch:

“Painting the rainbow flag at crosswalks? No mow May?!–”

The second man, thinking no one was nearby says, as I turn the corner, from dog toys and collars to dog food and treats:

“He’s a f*g and he had two moms–how unlucky can you get?” He chuckles and shakes his head, waiting for a reaction from the blue-eyed man, who doesn’t give him one because he sees me with my tattoos and queer haircut, discerning that I am likely “one of them”:

“Well, you can do whatever you want–the LGBT-whatever, but don’t mess with my lawn, Seren,” the first man says, and they both laugh together in collusion, thinking they got away with the slur–until I walked past both of them:

“Well, I appreciate the experiment of not mowing for a month,” I say over my shoulder as I push my cart from dog food to the pine shavings pile at the end of the poultry feed aisle, rolling my eyes: “And it’s not harming anyone; it is helping the planet…” They are quiet, at least, but my words are lost on them.

No one listens to the opposition’s view in this battle of extremes–in this moment of utter polarization.

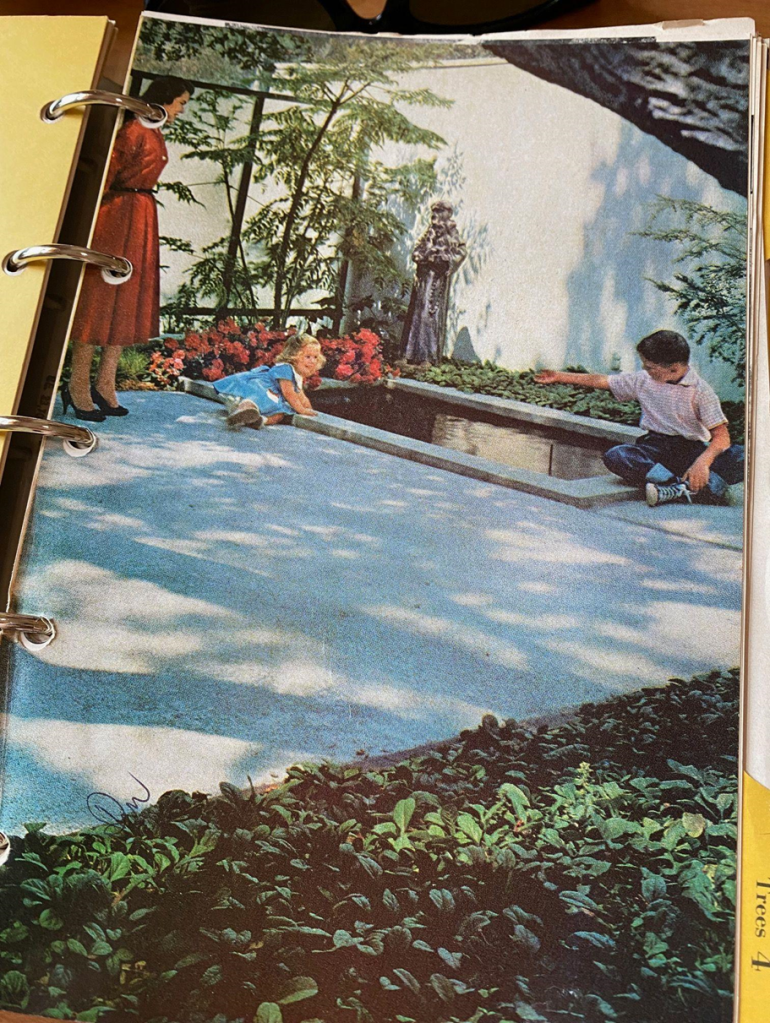

But the suburban conformity the white men at TSC relished as “better days,” were not so for most people. As the images from Better Homes and Gardens New Garden Book (1961) show, the suburban lawn of the Post-World War II era in the U.S. reified heteronormativity, class mobility through consumption, white supremacy and racism through systemically racist practices such as red-lining, and overt sexism. In 2014-24, the years I’ve lived in this bastion of suburban normativity, I’ve experienced sexism and queer-phobia.

No one outright says it to you: “Dr. Bly, you and your people don’t fit in.”

“All are welcome,” one city slogan reminds us, and the diversity here is real, so they can’t say that–they would be outcast themselves. The NPR-worshipping white liberals next door would cast them out for not conforming to the comfortable liberalism that pervades in the Heights.

So they beat me with their “laws,” “rules,” and hidden sexism, racism, and homophobia. The Cleveland Heights standard-bearers, those white men who longed for more homogeneity in the Heights and had longer histories in the city, were barely able to handle grass longer than six inches. Even the city’s first ever mayor, while elected by residents, was not welcome by these captains of patriarchal normativity because he is queer.

The weapon they used was the six-plus-inches of No Mow May.

Below images from Better Homes and Gardens Garden Book, (Des Moines, Iowa, 1961).

Many of the people in my neighborhood of lower-to-upper-middle-class educators, artists, nonprofit professionals, city employees, and wage workers also embraced NMM. I went on with my life, not thinking much of mowing vs. not mowing. I followed the system that I developed a few years ago, only doing so two to three times a year, adopting the principle Robin Wall Kimmerer (and her graduate student) learned more than a decade ago, and described in Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants. Using sweetgrass as their subject, they tested the hypothesis that when it comes to grasses, if you ignore them, they will die. Likewise, if you overwater, over light, over tend grasses (and this applies to most plants and living things), they become weak and perish.[2]

Below: “Rose: Floribunda,” from Better Homes and Gardens Garden Book, (Des Moines, Iowa, 1961)

A neighbor over tends the grass, making for undesired bleached out patches (photos by the author, July 2024)

It turns out that just the right amount of tending of sweetgrass makes for a lush crop. Americans don’t plant sweetgrass, and I have no idea what type of grass is in my front yard, as it was here when I bought the house, but as I watch the neighbor across the street edge, trim, mow, and cut (likely dumping some chemical on the grass to make it turn electric green), I see that too much “love” of boring suburban grass, makes for nonconformity of the GREEN, as burned out areas surface on their lawn.

Nature, in this case the grass people cultivate as lawn, doesn’t care about humans’ perfectionist pursuits. Plants are not widgets; they are not machine-made. They are alive, they are life.

“My lawn has white spots! What product will I buy to fix it? What will I do?!”

Naomi Klein told us back in 1991 that myths around beauty, perfection, and ideal bodies and beauty drive us to behave as consumers. Her theory is applicable to the lawn.[2]

“Which product/chemical will fix the white spots on my lawn?” a desperate lawn-lover might ask, only to spent $100 at Home Depot and the weekend hours “fixing” the “problem.” Environmental historian Ted Steinberg’s research historically details the products (seeds, fertilizers, soils, and chemicals), equipment (mowers, edgers, blowers, and trimmers), and—most notably, time, that the aspiring lawn gardener-perfectionist needed for achieving the greenest, lushest law on the block.

Time is our most valuable resource as humans. In the 1930s and now in 2020-present, amid the dire economic and societal ethos (of hate) of current historical moment, quiet, “free” time is even harder to find. American students always want to teleologically [3] assert that socially and culturally things progress over time. They believe the lies of the European History they have been taught—that, “thanks to the industrial revolution, Enlightenment (humanist) ideals, and science, everyday the world just gets better and better!” Not so for most of us.

By the 1950s, the average time Americans spent on lawn care was one to two hours per mow, depending on the size of the lawn and the equipment used to tend it. In suburban developments such as Levittown and Willingboro, both in New Jersey, men spent many hours per week making their lawns green, trimming hedges, making their “outdoor living room” as perfect as possible. A sociologist of the day, himself a resident of Willingboro, noted that the “pressures of lawn culture” are a “pervasive system of social control that [everyone] accepts.”

Another man of the 1950s said unabashedly: “It’s all lawn now… I don’t do as much reading; I have no time. It doesn’t bother me.” [4]

As a single parent for the last 10 years, working multiple jobs has been the norm. Spending time on my yard based on someone else’s more privileged judgment does bother me.

The hegemony of lawn culture is irksome because I want to read, socialize with friends and build community. Not fight with neighbors over the length of my grass, or whether or not my hens cross the street on occasion.

Above: “Lawns” from Better Homes and Gardens Garden Book, (Des Moines, Iowa, 1961)

My “free” time is already limited. At the peak of my hustling, from January to May of this year, for instance, I was working one full-time job and three part time ones, sometimes leaving the house at 6 a.m. and not returning until 7:30 p.m. after day job 1-day job 2, and one hour of teaching yoga (side hustle 1) on the westside. I was nonetheless making $20,000 less per year than I was making in 2019 before the pandemic. By May 2024, I had no idea whether it was “Mow May ‘24” or “No Mow May, the Sequel.” When you are trying to survive, petty issues like the length of your grass are usually at the bottom of your list of priorities.

It is therefore typical for me to be three-four weeks behind everyone else on the lawn front because I’ve been on an academic schedule for most of my adult life. April and May are nose-to-the grindstone grading, communicating with graduating students, and/or those who are behind from being overworked due to parental responsibilities, multiple jobs, and any number of traumas, particularly those we’ve all been enduring since 2017. Even though there are other educators on my block, they are married, heterosexuals who share the responsibilities of homeownership, which, in spring and summer, means a lot of lawn care.

Yet, to grass worshippers, nothing matters more than whipping that green growth into shape. They don’t care about my crammed schedule; it’s “Get to work, loser! Your grass is too long.”

Such was the case this year, when I received a notice from the city that this May, my lawn was more than six inches tall.

The violation essentially said: “Mow it and the city won’t fine you.” What my hateful neighbors don’t know is that by the time the notice arrives with its deadline, I’ve already put “get gas for mower,” and “mow!” on my “to do” list. I don’t need anyone to tell me to mow. It’s a matter of finding the time.

Over the course of ten years, I created a system for caring for the property on which I live, along with other plants, trees, and animals (domesticated and otherwise) living here with me. As the lawn goes, my system is as follows: wait until late April or early May to mow, and then cut the grass and ignore it until it gets long again. In the meantime, it becomes tan in color. I never water the grass, but I do water and feed the trees on my property, and water the food and medicinal plants, some of which are indigenous to the ground on which my house sits.

Above: FLORIBUNDA! A bee takes nectar from a patch of burdock in the author’s backyard; hundreds of various bees, insects, butterflies, and birds come and go each day (photo by the author)

A mini patch of Hiram, OH’s OPN Seed’s Bee Lawn Mix breaks through in the author’s front yard (photo by the author)

As of mid-August 2024, I’ve only mowed once. As my “to do” list indicates, I own a gas-powered Craftsman mower. My mother passed it on to me when she moved into a smaller place, where the neighbor mows the patch of grass between them.

I know using a gas-powered lawn mower for one hour is equivalent to driving a car for 300 miles, so I limit use. Right now, I cannot afford to buy an electric mower, and even if I could, it seems like another kind of waste to get rid of a mower that’s just five years old and was used for just one summer by my mother before she passed it on to me. I could sell it and put the money toward an electric one, but that just moves the gas mower to another yard, where it will still spew 300-car miles of emissions, likely for more than three hours a summer as I’ve been doing.[4]

In the last decade of single, queer-female homeownership, I also learned how much the homogeneously green, conformist lawn cost the planet and the plants, animals, people living on it. Mowing and leaf blowing alone create unsafe environments for birds, blocking mating and other communication calls, disrupting insect habitats, decimating wild plants and flowers like milkweed, the latter of which attracts the monarch butterfly. Moreover, blowing lawn clippings, dust, and pollen around when people are already suffering from seasonal allergies also seems counterproductive to a healthy environment.[5]

May-July 2024, The Aftermath of “No Mow”

A year later, living as we are amid an enormous backlash against women’s rights, female rights, queer rights, Black civil rights, immigrant rights, and–more to the point, the rights of birds, butterflies, frogs, and insects, the mayor of Cleveland Heights and city leaders are suggesting “Grow More May.” The idea is to get homeowners to have less grass and plant more indigenous plants, as well as vegetables, even putting forth potential plans and grants for residents interested in planting a front yard garden.

Steinberg tells us our late 19th and early 20th century “ancestors living in blue collar suburbs from Cleveland and Pittsburgh to as far west as Los Angeles, favored functionality [over] aesthetics… as late as the 1930s, working-class suburbanites–struggling to put food on the table–micro-farmed their property, growing fruit or vegetables and raising chickens.”[6] The idea of growing and/or raising food to make ends meet was a reality for my family during COVID. On financially tight weeks, as the cost of food continued to rise and my financial situation continued to wane, I could always tell the kids to make some eggs and toast for lunch. “Add some basil from the front porch for some green,” I could add in the spring and summer.

During my decade of single-homeowning, my goal has been to make the most of the land in my care, creating spaces that attract insects, plants, and animals. Never did I know that this plan would be controversial, that I would be threatened by the neighbor to my west over it. Nor did I predict that my plan for my yard would result in a three-inch thick file of “violations” for doing just what the Mayor and city officials are currently promoting (in part due to my neighbor, who made good on his threats, using connections with the Lawn Police Department since he was a city worker). In 2014 when I moved into my 1930s colonial, I didn’t imagine just how much conformity and suburban banality were drilled into my educated neighbors.

I studied the heteronormativity of the Post-World War II suburbia; I understood that the cookie-cutter perfection of the lawn as a prime signifier of the “American Dream,” first established in 1947 in Levittown, New Jersey as a planned suburban community. Many more would emerge and become available–thanks to red-lining, to mostly white people, after World War II.[7]

The Federal Housing Authority (FHA), a New Deal-era agency established in 1934 to aid new home buyers get bank financing. FHA loans insured 20-year mortgages for 80% of the purchase price. A “whites only” policy was enacted through a system called redlining. Using “redlined” maps as their tool FHA loan officers, city government across the U.S., and the very U.S. government colluded in systemic racism that continues to shape generations of people. le FHA access.14

Richard Rothstein explains the guidelines in The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America:

“Racially mixed areas were also deemed too risky, as well as white borrowers in white areas near African-American neighborhoods. However, a white neighborhood near a Black one could avoid risky status if a substantial physical barrier separated the two, such as a highway, wide boulevard, wall or deep concrete culvert. FHA guidelines also favored suburban over urban areas and the preservation of segregated public schools, justified as a means of maintaining racial harmony and property values.” [15]

So, always remember that this “dream,” which US-Americans across race, class, and gender fought for (i.e. against “tyranny” and “fascism” in Europe and Asia) was only available to white, heterosexual couples, who unabashedly took the spoils of the GI Bill and set clear lines of demarcation between themselves and their barely diverse neighbors, who were made to be “other” based on the care and maintenance of their US-American lawns, cookie-cutter-uniform homes, 2.5 children, and 1.5 automobiles.

In my “Noble” neighborhood, as it is sometimes called because it is bordered by Noble Road, which heads north, to Erie, and through East Cleveland. “Mapping Inequality: Redlining in a New Deal America (Cleveland, Ohio)” shows the historical nexus of white supremacist racism on my once Italian-dominated street, which, according to the mid-1930s document, was at the nexus of the green zone. In the 1930s, this meant that home values were meant to increase due to the number of white families living in the neighborhood. Indeed, my neighborhood, my very yard, was “BLUE,” at the time–not GREEN, or “best,” as the image below indicates, but “still desirable.” To some of my neighbors, BLUE is like getting a solid B on the school group assignment, even though you worked sooooo hard trying to make everything perfect.[8]

Likewise, the disheartened lawn conformist may pine: “We are so close to the A+ of the GREEN zone! Maybe if we mow more, tend to the roses a little better…” While my neighbors aren’t intellectually conscious of the history of red-yellow-blue-GREEN-lining, I am aware of the consequences of not conforming to the norms that are rooted in systemic racism and sexism. Indeed, before the current lawn-perfectionist moved in across the street, my queer, bi-racial family and I were reminded at each lawn transgression “You who don’t belong here,” with their ubiquitous refrain:

“We’ve lived here for more than 50 years.”

This was an Italian neighborhood; they were Italians.

They not only belonged here, but they also made the rules.

Once, before the neighbor to the west threatened me, he attempted to clean the side of my house with the Italian husband’s pressure washer. The old man, who watched everything from his front porch, yelled loudly toward us as the spray splashed back at us:

“No! I don’t want my equipment to be used on that house!”

The white man who would eventually threaten me in 2020 tried to cover for the queerphobic racist: “He doesn’t mean it, he’s just old.” As if I hadn’t heard Old Italian’s racist slights before from my own front yard when my Black friend with the good job and Mercedes came over, or when my mixed-race daughter put the trash out a day early, forgetting it was a holiday week.

Then I heard slurs that I won’t repeat.

Imagine yourself at your worst, in your ugliest of stained down jackets (because it’s March and it’s still cold in the CLE), hair askew, face shielded only by sunglasses, work pants (the Carhartts with the paint stains, the ones everyone now compliments you on) slipping off your skinny ass. Now imagine that the Italians have been stalking you, waiting for you to open your garage to reveal how horrible you are, how dirty. Imagine that picture comes back to you on an official City of Cleveland Heights Ohio communication.

Marshall Law over grass uniformity, hens out of compliance.

I continue to pay (taxes) for my own oppression.

GREEN

GREEN

GREEN

GREEN

GREEN

Between 1935-50, my street and those classified as the “Noble Neighborhood,” had the potential to go GREEN, tucked, as they were (and I am) north of Mayfield, on the edge of Forest Hill Park, west of Noble Road (but–gasp! a mile away from East Cleveland), yet–just a block or two away from the Inglewood Historic District.

Photo by the author: screenshot of the Noble neighborhood in the late 1930s (see https://dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/redlining [accessed July 28, 2024])

GREEN?

Today, in a neighborhood more diverse than ever (a truth for which I am very grateful), peace is elusive to those who don’t conform to the GREEN of the lawn. One of the many slogans of the city to which I pay high taxes is:

“ALL ARE WELCOME.”

This is not what the former Cleveland Heights residents I overheard in the pet foods aisle, complaining about Mayor Seren’s projects—white, male, middle-class, with good jobs and wives and offspring, were loudly expressing. It is not what the old Italians (now gone) put forth whenever a person of color or outwardly queer person (me included) came to my house.

And for daring to live alone, own hens (that do occasionally cross the road), subvert the lawn, I have been threatened, bullied, lied to, harassed by city employees and neighbors, some of whom were on the city payroll at the time of their threat-making, particularly those (thankfully) gone, who judged my visitors like a surveillance team from their porch directly across from mine. Now I’m surveilled 24/7 by a neighbor’s ring camera; there’s nothing I can do about the non-consensual monitoring of the actions of my household. I was on camera constantly when I worked in medical marijuana, but that was work.

So, I point a camera back, reflecting the paranoia of neighbors who might do better in Strongsville, Westlake, Solon, or Orange back at them, but I don’t spend my time reviewing footage for “criminals” or “rule breakers,” I live my life. Which I will continue to do in a the exact ways that I deem necessary for life on this planet at this violent, unpredictable moment in world history.

As for the Heights, it’s “liberal” white people with their suburban lies, the City’s mowing dilemmas, disdain for diversity, queers, and single homeowners: I’ll continue to tend to my biggest investment from afar. My place is on its way to being a rental property.

Of course, Pappa-Heights must approve all properties before they become rentals. Given that the top Daddy is a queer man, I’m certain he will understand and approve my application given all of the harassment I have documented over my time attempting to live in community as a uniquely talented individual in Cleveland Heights. For this, for being single, perhaps, being queer, has made living here as a single person, among these neighbors untenable for me.

In the meantime, I’ll continue to subvert The Lawn, one of the most sacred spaces of patriarchal suburban cis-hetero conformity. Yes, I intend to queer-the-hell out of it; forever.

Above: A newly emerged butterfly dries its wings for 45 minutes in Dr. Bly’s backyard

The author’s front yard; a neighbor recently gave them the best compliment: “I love your house; it’s a manifest[a].”

Citations

[1] In the City of Cleveland Heights, if one’s grass is more than six inches high, it might go unchecked if the resident’s neighbors don’t notice nor care. If, however, your neighbor is unwilling to communicate with you about their concerns, they take a photo and send it to the city via email. The city uses that person’s photo on the form letter they send to you as a “warning.” This has always felt unfair and inequitable to me.

Case in point: neighbors on a street to my north have hens that roam their street and happily go on their way. My neighbor uses infractions (some explained here) as a weapon. In 2020, while this man was a city employee, he threatened me verbally, stating: “Going forward it’s going to be very hard for you to [raise your family] here.” After the letters from the lawn and chicken police began to stack up, I consulted an attorney who suggested I contact my council person, which I did. Turns out my letters to the city and the media (this, combined with his own record of aggressive and inappropriate behaviors at work) got him fired.

[2] Klein, Naomi. The Beauty Myth: How Images of Beauty Are Used Against Women (William & Morrow: 1991), see the introduction, but read the whole book.

[3] Google “teleological” and think historically.

[4] Wall Kimmerer, Robin. Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants (Canada: Milkweed Editions, 2013.

[5] Steinberg, Ted. American Green: The Obsessive Quest for the Perfect Lawn (New York, NY & London: W.W. Norton & Company, 2007), see Part I. Origins, 3-83.

[6]Publications and Facebook posts from Quiet Clean Heights, https://www.facebook.com/groups/3495570830662146/?paipv=0&eav=AfZwGxeJ_YNox4CAt5gnV5IK4mmaFcx6xBXH1D0_yLrs9ipC5urq-LWel_H5sPq4-6s&_rdr (accessed July 28, 2024).

I am not addressing the use of chemicals here because that is a subject I plan to address thoroughly in another post. This said, the irony of neighbors dousing their lawn with chemicals to keep themselves “protected” from pollen and weeds like dandelions is never lost on me. Dandelion is a medicinal plant, an anti-inflammatory, with the potential to cure cancer. Synthetic chemicals such as those in RoundUp are proven cancer-causing agents; many pesticides have “forever chemicals” in them, meaning if you dump them on your lawn, they are there in the soil not matter what you (or a future owner) choose to do in the future with your property (land/soil).

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid., Steinberg, 8.

[9] Ibid., 12.

[10] Ibid., 16-37.

[11]Mapping Inequality, originally published in 1938 as a tool for determining where red, yellow, blue, and green lines were literally drawn by city municipalities, banks, and real estate agents looked at these maps to make loans, city laws and rules, and to sell houses to people based on their racial identities. (accessed June 19, 2024).

From https://dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/redlining (accessed July 28, 2024):

In the 1930s the federal government created redlining maps for almost every major American city. Mapping Inequality lets you explore these maps and the history of racial and ethnic discrimination in housing policy.

Redlining was the practice of categorically denying access to mortgages not just to individuals but to whole neighborhoods.

Between 1935 and 1940, an agency of the federal government, the Homeowners’ Loan Corporation, graded the “residential security” of thousands of American neighborhoods. By “security,” they meant the relative security or riskiness of those areas for banks, savings and loans, and other lenders who made mortgages.

[12] Images not taken by the author are from Better Homes & Gardens Garden Book: A year-round guide to practical home gardening (Des Moines, Iowa: Meredith Publishing Company, 1961).

[14]Richard Rothstein, The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America 20- 23 (2017).

[15]Ibid.

Leave a comment