Lyz Bly/DRB, Ph.D.

INSIDE FRONT COVER: Bread and Roses, 2020 (PHOTO by the author)

Be nice to budtenders: a marijuana memoir

Lyz Bly

2023©

Thank you

Barbara Erhenreich (1941-2022)

And

Sylvia Federici (1942- )

Contents

Preface—6

Introduction—9

1. Dream Job—12

2. Enter: Production, Industry, and Change-chan-chains—24

3. Bob is Dead (no one cares)—42

4. Piss Factory—49

5. Architectural Digest—61

6. Dude-Bro Cult—75

7. Changes (Turn and face the strange)—88

8. Downtown (Forget all your troubles, forget all your cares)—110

9. A Rose! Reprise—119

Notes—133

Preface

Emma Vignola, Ph.D.

DRB’s account of working in the medical cannabis industry during the COVID-19 pandemic, in Cleveland, Ohio, brings us with vivid detail into a world of possibility curtailed by corporate exploitation. The account takes the form of memoir in parts, grounded firmly in DRB’s positionality as a white, female, gender queer member of Generation X, as a writer and activist with a doctorate in history, as a single person with a young adult daughter living in her home. However, through the lens of her identities and experiences, it is simultaneously a collective story of worker resistance to corporate forces, of workers refusing to accept that company profit should come at the expense of our well-being.

At its core, Be Nice to Budtenders is about the perils of capitalism’s takeover of cannabis, a pressing issue as a growing number of U.S. states have legalized both medical and recreational marijuana. In DRB’s first weeks as a patient care specialist at the dispensary, we read about the non-hierarchical comradery between co-workers, a palpable sense that they were making something new, finding meaning in their work providing customer-patients relief for a range of physical and mental ailments. Unfortunately, as DRB notes, exploitation of the plant for profit includes exploitation of the workers who grow, package, deliver, and sell it. We experience the teamwork that breaks down under the pressure of corporate employment practices, the sense of disunity that sets in.

The work is inherently both physically and emotionally demanding – counting, repacking, and carrying hundreds of pounds of cannabis and cannabis-derived products around the dispensary, interacting with people with a mix of health needs, mixed sometimes with the toxic behavior from customers that workers in public-facing service jobs in America often face. These all bring risks for workers’ mental and physical health. But corporate-driven precarious employment conditions – rooted in unbalanced power between workers and the employer – worsens the harms of these physical and psychosocial work conditions. Low hourly wages, understaffing and one-sided changes in scheduling, encouraging workers to spend less time with each customer, breaking rules and regulations around training with a focus on profit – all of these employment practices that DRB cites create threats to workers’ well-being.

Because of its federal illegal status, research and policy on the health, safety, and well-being risks of work in the cannabis industry is scarce. But lessons can certainly be learned from other precarious jobs in agriculture, logistics, and retail – as well as from this text. As researchers and policymakers call for greater attention to and regulation of the conditions in this industry, Be Nice to Budtenders is a rich qualitative source urgently needed in the conversation. People of color who have been disproportionately harmed by the racist, classist, and ineffective “war on drugs” are now being prioritized for employment in this industry. Because of occupational segregation, workers of color in this country are already more likely to experience workplace hazards and poor employment quality than white workers. This means that the industry’s potential for worsening racial inequities is there – as is the potential for tackling them. All workers in the cannabis industry, but especially workers of color, would benefit from union protections, because there is little reason to believe corporations will voluntarily improve workers’ conditions and self-regulate. Despite strong corporate resistance, cannabis is among the few industries experiencing unionization gains in recent years, as workers are reaching out to unions themselves.

More broadly, through the lens of DRB’s individual experience, we gain insight into a collective story of the pernicious “hustle” at the center of work in America, or the ways we internalize and deal with austerity politics and the myth of personal responsibility. We read about the forces that led DRB into this public-facing, insecure, hourly job during a pandemic in the first place, related to what was (not) made available to people to protect themselves physically and economically during the crisis, and about what it was like to work in a job whose social value is not recognized materially in the form of a living wage, benefits, and health and safety standards. As DRB writes, “I understand the lies of the American dream even better from my time at the dispensary, namely because I mostly liked the work, mostly enjoyed our patients, mostly liked my co-workers, but doing an excellent job, showing up every day no matter what was going on at home or with your own body wasn’t good enough to earn a livable wage.” Be Nice to Budtenders is about refusing to buy this lie, even when quitting is the main form of power at your disposal. Though obstacles to large-scale change remain, we continue to see the effects of the pandemic-driven national reckoning against low-quality jobs and renewed interest in labor organizing. May the struggles of workers in the cannabis and other industries help shift the massive imbalance of power between workers and employers in this country.

Introduction

Sixteen and time to pay off–I got this job in a piss factory inspecting pipe –40 hours, 36 dollars a week—But it’s a paycheck, Jack – Patty Smith, Piss Factory, 1974

ABUSE OF POWER COMES AS NO SURPRISE.–Jenny Holzer, (Truisms) 1990s

Je ne jamais travellier pas.-Situationniste Internationale (Paris graffiti), May 1968

There’s a moment in every worker’s life when they wake up and decide that they are going to tell the truth. We’ve done it in many different ways over the 500-700 years that European and American capitalism have been exploiting the planet and every living being on it.

We strike.

We protest.

We unionize.

We throw bricks.

We break tools.

We drag our feet.

We dash the curry, like we’re not in a hurry.[1]

We state our disillusionment, our anger, our despair in different ways.

A writer, a queer, an activist—words are my weapon.

This book is an account of the medical cannabis industry in the Midwest, in Cleveland, at the center of the city at an auspicious time in history… and at a transformational time in the history of The Plant.

Just as we must change habits wrought from industrial global capitalism to save the Planet, we must save the Plant, cannabis, from patriarchal capitalism because the White Capitalist Man is learning cannabis and that means he’s exploiting it and everything around it, including the workers who labor to grow, package, deliver, and sell it.

A historian, I remind you that this is the same plant that the German Christian elite white men in the Rhine region of Germany stole from us as early as 1342, when the elites in charge went to the Black Forest and destroyed the peasant witch wisdom thriving along the rivers running through the Southwest region of Germany, the place of fairy tales, witch lore, and ghost stories. There, the German Catholic Church men, the Guild men and the militias protecting both, destroyed the female-peasant cultures blooming in those forests.[2]

Then, like now, He was afraid not knowing Truth.

The truth of birth and death and pain and suffering and joys and celebrations, most of which were all tied to the seasons, the earth’s elements, the sun, the Moon, the planets, the universe.

All of these things were stupendous in and of themselves. There was no need for God.

So terrified of the Truths of life, death, sex, illness, healing in those lush forests of trees, mushrooms, plants, berries, and nuts, he rooted them out entirely. The witch hunts began, which meant destroying the knowledge, which meant destroying the people who held it in their bodies, their minds, their hearts… the female peasants, the witches, the midwives. We don’t know exactly how many peasant-healers were killed in the genocide against “witches,” which in Europe began in 1342 in Germany, the same country where the industrial revolution was born.[3]

We have court records of some of the witch trials, but the guild member militia often took peasant dissent into their own hands.

When they took them the peasant people, the midwives, they took their cannabis.

This book, however at times daft it is, is written in their honor. For the witches of weed.

The white man will not take our medicine again without giving us credit… And reparations.

Love, DRB

The queers are now in charge, 4.29.2023 (My last day working at A Rose! Cleveland)

[1]M.I.A., “Dash the Curry-Skit,” Arular (Interscope, 2005).

[2]Sylvia Federici, “The Great Witch Hunt in Europe,” The Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body, and Primitive Accumulation (AK Press, 2013).

[3]Ibid.

Chapter 1: Dream job

It’s just the right temperature on Mike’s patio, where I’m seated with Karen, Mya, and Laura. Manny leans, dreamily stoned on the patio railing behind Laura, swaying a bit with the smell of ribs wafting from inside the boxy colonial in the eastern suburbs of CLE. This is not an official work gathering, we bring the food, Mike and Alicia, until now, referred to at work as “the wife,” prep the grills–one for the ribs, then a second, to grill tofu steaks and vegetables. Mya grabs the brush from Alicia as we walk up with bags and a big silver pan of marinating plant food; “I got this, sis. I’m Mya.”

“Hi Alicia,” my niceties begin…

It’s warm, but breezy and quiet on Mike and Alicia’s corner house in Richmond Heights. Mikes giving us a tour of his garden, which consists of a few rosemary plants and a fledgling tomato plant in a tiny grow tent, which is in arm’s reach of the back patio. Mya and I look at each other, eyes-wide, for a second to indicate our nonplussed attitudes toward the garden. We are fond of Mike, but he’s a braggart and the way he talked about it at work, you’d think he’d have a crop of tomatoes in a greenhouse.

We pass a blunt–Lemon Slushee, Mya and me, as we walk through Mike’s grassy backyard. It’s a boring, rectangular piece of lawn. Uniform. Green. Mya and I make a game of following Mike in single file, through the last leg of the grass-green, up the steps to the patio where Laura, sunny-faced, blonde, abundance, is seated with Karen, our hippie-new-age suburban mom colleague from a white outer-ring suburb on the Westside. As we settle into the two empty chairs, Mike shuffles behind Laura, “So, there’s soda in the blue cooler. If you have beer or alcohol, put it in the white cooler… food’s inside.”

Laura is the manager and I’m just five months into this side gig at A Rose!, so when Karen extends her live resin Orange 43 vape to me, I look at Laura.

“Is this really ok–with ‘diversion’—I make the air quotes—and all, I mean?”

She looks at me with the brightest, bluest set of eyes I’ve had reflected back at my own, open as they are, blue-green, “We can because we need to make something new. We have the power to change everything. Now it’s our time.”

I shrug and unscrew the lid from my pineapple habanero gummies and put them next to the other offerings, gesturing to Laura because I didn’t know what else to say in response to her broad statement, as much as I agreed with it. Moy would tell me the same thing months later when things were much more dire, but in this moment in the sun on a Sunday afternoon, I wanted to melt into the chair with these people I’d come to know and love in a short span of 150 or so days.

In this work of serving people, of customer service, of Patient Care Specialist, you know and see every aspect of humanity, most of it is humbling and beautiful, some of it is toxic and abusive. It feels like living in an abusive household. The customers, especially the men, could come in at any minute and stand over you with their girth, call you “sweetheart” in the cruelest tone, talk over you with the other bruhs in the room, or straight out threaten you. In our workplace, the medical marijuana “patients” were the unstable, emotionally violent step-parents that came and went with their actions, which were left largely unchecked.

So we bonded like siblings sometimes do, trusted our corporate oppressors like victims of Stockholm Syndrome, and–yet, if anyone spoke out of turn, spoke in terms that didn’t meet gentile middle-class white social norms, they were slapped. I will tell you later how they slapped Ramona and subsequently emotionally thrashed the rest of us. In protest, we quit, almost every one of us, one by one by one…

But we’re at Mike’s by choice on this sunny June evening of 2022 and Manny is striding toward the sliding-glass after Alicia’s call of “RIBBBSSS!”

From the patio we hear him say, “Ah! And 7-layer Mexican dip!!” and then, calls out past us toward the garage: “Ramona, Eli, Mike! FOOOOOOD!!!”

The myrcene that makes medical cannabis patients–and this group of stoners, hungry is kicking in for all of us. It was after 4 p.m., so indicas–which we get patients to remember are restful, or as we said to the new ones–who always laugh, “in-da-couch,” were burning. This meant that it took just one prompt for the concentrate burning garage dwelling dabbers to come to light with the dank, earthy, musky smell of Klutch’s Blue Cheese strain trailing behind them.

“Ramona!” I say louder than I intended to, she’s chill right now, with only ribs on the brain, “I don’t think I realized you were in the garage…”

She chuckles and says, “Yeah, DRB, you know black people are just not comfortable sitting out on display smoking weed…” I laugh with her and then feel the myrcene myself; “I’m going to get some chips, anyone want some?”

Mya, fair-skinned, tall and willowy, buoyant, is halfway to the grill to put our veggie kebabs onto plates for the two of us–everyone else has heaps of animal parts glazed in some kind of sweet-hot BBQ sauce, “Mya,” I say, “Please grab chips and salsa on your way back to the table.”

“Bam! Here you go, Sister,” tofu kabobs and tortilla chips with hot salsa bend the cardboard plate as it drops in the center of the table.

We dive in as Mike scans the table to see if anyone needs anything. He’s a former Marine, trying to live a normal life after the Iraq war and a stint in chaotic Haiti during the revolution of 2004. He’s not the only one with PTSD, it is the diagnosis of many of us working at A Rose!. Often his behavior and comments were triggering to the females and queers working with him. Once I almost had to have a gender studies 101 conversation with him over his comment to me when I mentioned my plans for a date with my friend Rico.

“Ah—Dr. Bly is getting some later!” He attempts a joke with Mya behind reg 2 and no one on the sales floor.

“He wishes,” I say blandly, quietly because I see Mya tense up at his comment.

I’m off at 2 p.m. that day and I ask Mya to come downstairs with me as I want to talk with her about Mike’s comment away from his ears. “Mike, Mya’s coming down with me to put some CBD balm on my back,” I say so he knows he’ll be alone on the floor for a few minutes.

“Ok ladies, enjoy,” he replies.

I sneer toward Mike, “Stop calling me a ‘lady’, please,” following Mya’s scowl at him, as we pass through the doors between dispensary floor and order fulfillment and then between order fulfillment and the back and basement doors, which “SLAM!” behind us.

“Mike keeps talking about our ‘booty calls’, it’s none of his business and the corporate training gave us specific directions on what is/is not appropriate at work,” Mya says, her voice firm, “and I’m 100% that that ain’t right.”

“I’m going to talk to him privately, but I get it if you want to tell Laura,” I reply because I know Mya likes to follow process. She didn’t have to tell Laura, though, because that afternoon our tuned-in manager heard his comment about my evening plans. She spoke with him immediately and that toxic masculine behavior stopped, at least until Brydon arrived to replace her months after the gathering at Mike’s house, where I’m back at my seat across from Laura, flanked by Karen and Mya, where plates are heaping with marinated tofu, zucchini, onions, red peppers, and mushrooms. I feel a sisterhood at work that I hadn’t felt since I worked in the restaurants in high school and college. And like the comradery

At the time of the party on Mike’s patio I was three years with a PTSD diagnosis that came as a culmination of things. Family-related battles over inheritances, trauma from being abused at work by colleagues, superiors, and–ultimately students, among other things, made being at A Rose! amid this crew feel healthy, almost reparative for me. I saw it in Mike, too, who was enthusiastic in his love of cannabis as medicine. He helped most of the veterans get their military discount of 30%, which in our early days at A Rose!, meant a lot as the lack of competition in the city meant the few dispensaries open could charge whatever the market would bear.

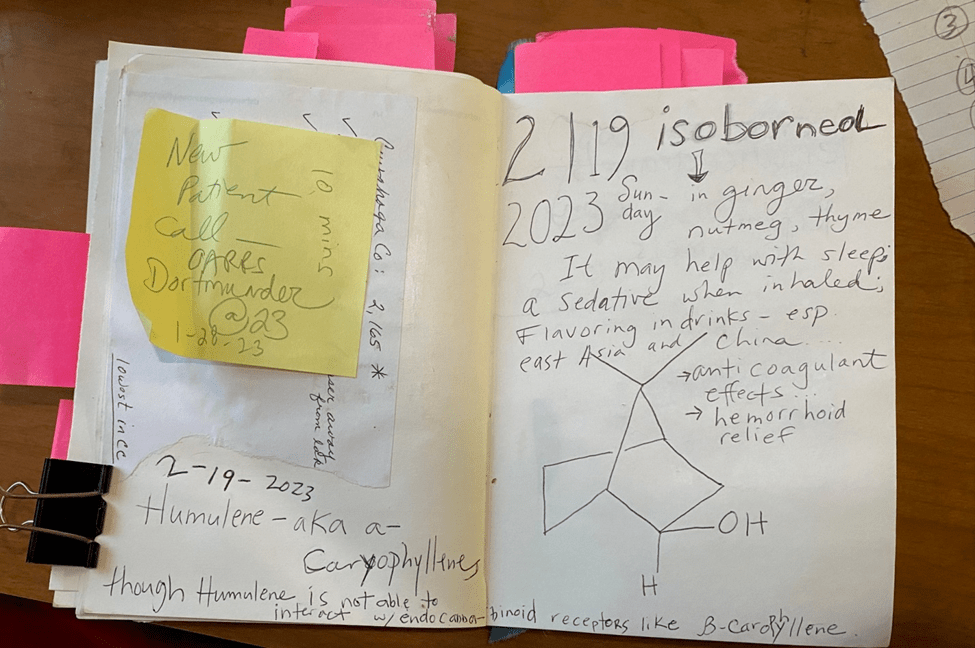

He used his own 30% discount to try everything that looked good to him on the menu. He wrote reviews, shared pictures of the purples, oranges, greens, and blues of Ohio-grown cannabis flower. He zoomed-in on the sparkly trichomes, describing the smells and tastes. I learned from him, and I learned from everyone. In these early days of my tenure at A Rose!, our curiosity and unique skills and diagnoses were central to selling medical cannabis to patients, most of whom were already on board with cannabis and had been using it medicinally and recreationally for years before it was legal, mostly to critical relatives and neighbors.

For some of my colleagues, having the medical designation helped to legitimize our jobs. The fact that the Ohio State Board of Pharmacy defined us as essential workers during COVID helped, but by the spring of 2023 when I left my 18 month stint at A Rose!, it was becoming clear that something was changing. The patient care specialists–those of us at the lowest rung of the hierarchy, were coached by management to move patients along more quickly. One new employee was told to limit the number of times a patient asked to see their medicine before purchasing.

“That dude wanted you to be his mother, Shelly,” manager Brydon tells her, “We gotta stop patients from changing up their orders. It’s wasting time.”

With these female people, and with Ramona, who’s inside sampling Mike’s spouse Amanda’s Good Housekeeping inspired spread of sides, it often feels like the communities we all grew up with in the dreams portrayed on Sesame Street, The Electric Company, and the ABC After School Specials.

In the “professional” jobs I’d held since the late 1990s, the ones my advanced degrees granted me access to, the stakes were different. The body was secondary to the mental and emotional output required in the grind of administrative desk work, its aches and pains tweaked back to life with the occasional massage or spa visit–a little “self-care,” if you will. The visits with therapists to undo harm caused by abusive bosses, sexist colleagues, homophobic donors, etc. were at least partially covered by the company’s insurance plan.

In the elite roles I held throughout my career I worked with people, of course, but it was the work of the mind. Before COVID brought us Zoom and even more remote work, being on a team meant sitting together for an hour or two, reporting on what we did or didn’t get done on our task lists, looking at calendars, and projecting into the future on what we thought we could get done and how much time it might take. At A Rose! the team entered and exited the building together at the beginning and end of the day. We carried 500-600 pounds of cannabis and cannabis-derived products up a tall flight of stairs, often with the help of a wheelchair lift, but sometimes–like mules, we dragged 50-60 pound bins up the stairwell from the sewage-smelling basement.

We counted every product together in the morning, we repacked it together at night, and took it back downstairs to a vault. The State mandates that, like all pharmacies, that the medicine be locked in a bank-style vault during nonbusiness hours.

After the cannabis was ready, we logged in to our POS system and the Ohio State Registry for Medical Marijuana, and people showed up to buy their medicine. The physical work was over for the morning, but the emotional labor began. At the time of the party at Mike and Alicia’s, in June 2022 we were a tight team who worked really hard and played really hard, sometimes together. There was trust among us, a sense of possibility in working for A Rose!, and an all-female, mostly nonhierarchical team of managers and pharmacists.

Eleven months later everyone sitting at the table, everyone in the garage except for Manny, and even David, the straightest and the white man among us, is gone. Like me, Mike has other income sources, like me, he needed the money to make ends meet, like me he left without another job to fill the gap. Our health–physical and mental, well-being, and sense of dignity is more important to us than paying the bills on time.

****************

The medical and recreational cannabis industry in the U.S. is in its nascence and in corporate terms, this means that employees must be “adaptable to change,” which means white corporate elites have permission to behave badly, irresponsibly, inconsistently, and, sometimes apprehensively, without consequence. Wage working patient specialists/budtenders, the lowest on the corporate rung, were to make sacrifices, work around broken or antiquated scanners, prescription label printers, and cheap office furniture, to be creatively resilient.

We were privileged to be in their presence, these new agents of The Medical Cannabis Industry in the State of Ohio.

Lucky to make $16.32 an hour while their Amerikkkan dream—their entrepreneurship was rewarded with bags and bags of cash, which were collected by thugs in vans a few times a week.

While I sold cannabis for an hourly wage and was sometimes treated poorly by patients, I was also always am a gender studies professor and a historian, primarily. This meant that demanding accountability was as vital to my work at A Rose! as it was anywhere else in the world.

Across the street from the dispensary, just two-three blocks away, I teach my students to speak up when they are treated badly at work, to hold their abusers accountable, to understand the history that got us to the point where people would consider voting for a person who would openly brag about pussy grabbing and tongue kissing women against their will, and then have a court of law charge him of raping a woman in the 1990s in a Bergdorf-Goodman dressing room.

And just as there are sexist and racist micro aggressions that invade our psyches and tell us that we are less than because we are female or black or queer, there are class micro aggressions in hierarchical wage workplaces. I learned this early on as a student paying my way through graduate school, as a young attractive female, my body was always up for grabs while I was slinging pancakes and sausage-gravy biscuits to hungover college students and cigarette and coffee addicted townies. Then I got angry, went to a therapist, became a feminist.

Now, a queer-feminist elder, when I get angry, when I see injustice, I attempt to make things right. This is one account of the cannabis industry. There will be more, I hope, because those of us who work in the early stages of the white man’s discovery and exploitation of cannabis will continue, but he cannot annihilate the community spirit of healing and joy and relief that it brings people. I saw thousands of people in my year and a half consulting to provide relief for every ailment imaginable. There were people in pain from car accidents, flawed surgeries, surgeries that were successful, but still painful; there were those who were trying to rid their lives of addictions to drugs like oxycodone, heroin, and Xanax.

The most difficult patients were those, like me, suffering from PTSD. My time as a PCS was during the COVID pandemic, so anxieties were high, but people were most grateful that the dispensary–one of four operating in the 20 mile radius of downtown, was open during the pandemic. The pandemic bolstered sales of medical cannabis; there are two common states for people during and after COVID lockdown: the anxiety and boredom of confinement for the newly remote white collar careerists, who missed the distractions of shopping, dining, weekend getting-away, and just having general autonomy from the responsibilities of home with partners, children, pets, dishes, shopping solo and masked for groceries, drinking way to many IPAs in the evening, binging on too much true crime TV on Netflix, and getting even more bloated and sluggish than before March 2020. The second state is the one I would come to know best during the three years of the pandemic: the physical and psychic stress of working with and for people during the pandemic.

A professor, yoga teacher, and budtender at A Rose! during COVID, I not only had to bolster myself every day to make it out the door, somedays leaving at 7:30 for the dispensary, then heading to CSU for office hours or a visit with my friend Stevie, who now not only taught in gender studies, but was director of the women’s center, where I camped out between 2:30-4 p.m. on Mondays and Wednesdays.

Occasionally, one of our more blue-collar worker white men patients would chide the PCSs for our cushy jobs. Gerry, 50-something, buff, blue eyes, waxed mustache that curled, was waiting too long for his Lime Sherbet half ounce, so he decided to tell me about my job at A Rose!

“Well this has to be an easy, fun job,” he tells me. “You talk about weed all day, stand around, listen to music.”

I might’ve been two months in to my work, but I still haven’t mastered dragging 12 large totes to the wheelchair lift we use to cart 100s of pounds of cannabis up and down the stairs to and from the enormous bank vault in the basement where we were required by law to store the cannabis when no one was on site. Nor had I mastered unloading all of the totes onto stainless steel utility shelves from ULINE, which, for no reason that made sense, had to have their doors on and locked while empty, again, when no one was there. The worst of the morning routine, if this doesn’t sound like enough of a physical work out, was the counting.

Imagine four adults, one of them is a superior–a manager, a pharmacist, or a shift supervisor, the other three are Patient Care Specialists (PCSs). Then imagine a 12 x 10’ room with a support beam in the center, the metal shelves, sometimes filled, sometimes empty on two sides, a desk in the corner, across from a row of mail slots with doors that open from the inside. The mail slots connect this little room–called “order fulfillment,” to the sales floor, so that PCSs can grab patients’ orders from a numbered mail slot connected to the register in which they’re working.

Then put the four adults, most of who are already “medicated” for the day ahead–but more directly, for the body pains that would come from lifting wide, awkward black plastic bins, and then stocking the dispensary shelves for the day. Imagine that all of this work, the carrying, the stocking, the counting must be done between 8:00 and 9:00 a.m.

Then consider that the opening pharmacist lives 45 minutes south of the city in one of the most elite ex-burbs that also happens to be in the Snowbelt. Oh, and she has five kids, all of whom are in sports and school.

Imagine yourself–knowing that you need to be a team member and pitch in in this overwhelming task, sitting in your car in January in Cleveland in an empty, trash-laden, urine-smelling parking garage at 8:10 a.m.

The pharmacist messages over Teams, this time, at least, to tell us there’s an accident.

By now, Ramona’s pulled up in her gray 2018 Honda Accord, bumping Jay Rock’s “Win, win, win, win–fuck everything else–win-win-win-win–these [n-words] ain’t shit…” and she rolls down her passenger window and she backs in next to my black 2020 Honda Civic Sport, and we each turn down our music.

“Hey–Mona’s caught in traffic on I-480, we’ve got probably ten more minutes,” I say as Ramona says more to me with her expression than her one word reply:

“Right,” as she looks at me with a combination of irritation and satisfaction at being already clocked in, sitting with the heat, music, and a blunt blaring.

I smile, roll up my tinted window, and blare, likewise.

Ramona has mastered the morning ritual, though. She has no nervousness about messing up with the counting and though she has some health issues that makes the work difficult on bad days, she makes up for it by either bantering with me and anyone else who chimes in about politics, the racist asshole we had to listen to yesterday while he complained about his live resin gummies, or by setting the vibe for the day with a good playlist.

I haven’t mastered any of it and I learn that if you miss-count you will get reprimanded. Once, Mona pulls me back to order fulfillment because we messed up the counts and, “I have to talk to everyone working on that morning.” I don’t cop to it, but on one particularly bad morning I was too overwhelmed by the counting, the packages of disposable vapes in brightly colored plastic, non-recyclable sleeves, required that you look at each bundle of five to make sure that someone didn’t forget to take the rubber band off, the system for knowing that unbranded disposables were supposed to be less than five per band.

Every day this was the routine, every day we were put on opening shift we did this ritual in the tiny space with four people and big totes of cannabis flower, gummies, infused honey and marshmallow cream, the extracts–budder, badder, sugar, shatter, resin, and rosin, packaged in expensively printed cardboard containers that were as much as five time the size of the tiny jar of precious (and costly) concentrated marijuana, the THC-laden drinks, and the thousands of vape cartridges, and disposables. There were as many as 250 products on the menu; imagine a sampling—15-30 of each depending on what was in stock, daily sales—most importantly, still depending on the grow-cycle of the Plants cultivars were “producing.” Imagine packing all of it up again at the end of the day and returning it to in reverse order to the basement vault for secure overnight storage.

This task seems especially enormous for me because, again, I’m not used to dealing with “things” in my work. Privileged, I’ve held careers built on ideas. Using the iPad (a tool for creativity in my life before A Rose!) in connection to counting products was a new skill. I was out of my comfort zone and nervous every time I saw the schedule and I was on the opening crew. Here’s the thing, despite my anxiety over the morning routine, I was always on time. Had I been late more often, they might’ve scheduled me for evenings, which I preferred. I’m not a morning person, I hate the counting, yet my responsibly worked against what was actually in my own best interest.

So when regular patient Gerry, a mansplainer type, was telling me about the ease of my job on a Monday at 9:15 a.m., I could do nothing but stare blankly back at him. In moments like these, when you have to stand on the other side of a counter from someone you don’t know and make conversation while the pharmacist moves their cannabis prescription from the steel shelf, puts the label with their name and the product number on the bag or jar or can and places it in your window for your patient’s approval, you learn to turn and say nothing, which at first is awkward, but later only becomes awkward for them because most people suddenly realize that they are being an asshole.

“Let me check on that order, Gerry,” I say blandly. I start to learn that I can punish patients who are rude by giving them nothing but the basics. They don’t get my occasional, “hon,” or “friend,” nor do they get my real eyes. I give them dead eyes, give them the routine:

“Here’s your Orange 43 2.83 grams of flower,” as I turn the jar upside-down so they can glower over it, or reject it which sometimes happens, then, “It’s $43.”

I lay the $60 in cash out for the camera above, making it easier for the person who has to review the footage if I make a mistake and forget to give change, which happens more than you would imagine. Then enter the amount into the POS system and hit “Done,” which spits out the cash drawer and two receipts–one for the patient, one signed that we keep, but never look at again. Still the State requires a signature, just like at the regular pharmacy and it signals the end of the transaction–well, at least before we staple the bag (another requirement) and send them on their way.

Gerry and I are silent through the end of the sale and he grabs his bag a bit more timidly than usual, he knows he’s crossed a line as the little bit of power I have as a budtender comes through. “Shit,” he may have been thinking, “Now I’m going to get skipped in line,” or “what if they mess up my preorder on purpose next time…” In the first year this bit of power meant just a little bit more in a less saturated medical cannabis market.

During my 18 month stint at A Rose!, the number of dispensaries licenses in the state grew from 58 to 131, and by April of 2022 we began to feel the competition from Ohio-owned and a few other nationally-owned cannabis companies. This is when everything at our location began to shift with the corporation and with the way in which patients began treating those of us serving them. The changes we experienced from the corporation and management were not surprising to anyone, though their obliviousness to our work conditions, which began to erode in June of ‘22, was despicable. most surprising to me was how quickly our patient interactions changed. most of the regulars still wanted to talk about the last strain they purchased, often comparing notes with us on its affects, terpene composition, or THC/CBD ratios, and they still updated us on the latest the problems they were having with their bosses and co-workers, how the family event they were on their way to the last time we saw them went, and the intimate details of their pain and suffering, but there was a new kind of cannabis patient coming through–the bargain shopper, the impatient stoner, the snobbier than normal concentrate connoisseur, the hustlers trying to find the cheapest tenth to mark up and sell on the street for too narrow a profit margin.

Most of the traumatic stories shared here are about those in the latter group, while the beautiful ones come from relationships with the regulars, but also from the desperation of everyone who came through the doors while I was working, because my time at Rise happened at some of the most difficult and traumatic times I’ve ever lived through. It’s terribly paradoxical that while Rise the corporation was making money hand over fist during this period of intense human suffering, the people making them the money, the PCSs, had to conjure every bit of patience and empathy to help [patients find relief with cannabis, earning just $16.32 an hour, while pumping through as many as 50 patients per shift.

At the time of the party in Mike and Alicia’s backyard, in early June 2022, our store’s General Manager Laura felt confident enough in her job to tell us that we could make our cannabis store, our relationships with each one another and our patients magical. We watched her model care and empathy with patients, sometimes counseling a PTSD patient who was triggered in the conference room, always listening to everyone with bright eyes and an open heart. Yet, by the end of the month she would be gone. She would tell us it was to help her parents with the family business in New York, but we knew that would be replaced by someone whose dreams were more centered on money.

By August, Laura’s team started leaving in waves.

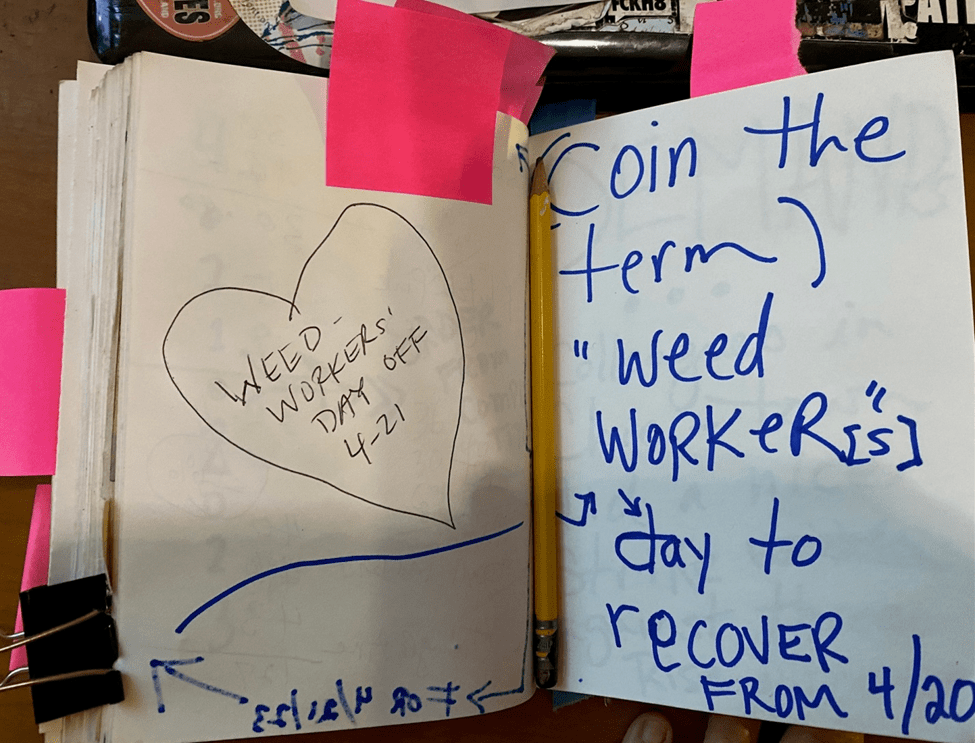

Now, of the 18 of us working there on April 20, 2021, only Moy remains. Moy is the only person who’s stayed since the beginning. They are also now the only person of color working there, the only outwardly queer person working there.

So this book is also about how corporations do significant harm to people, particularly the workers. In this way, it is a nod to Barbara Ehrenreich’s 2001 book, Nickel and Dimed: On (not) getting by in America. While much less expansive in its analysis of wage work, this text is an effort to document in memoir what it is like to work in the cannabis industry in Cleveland, Ohio during COVID, the economic decline of the 2020s, and the subsequent fallout that I saw daily from the ordinary cannabis users. Because Ohio is a medical cannabis state, I must protect the identities of patients by law, therefore, the accounts are true, but the names of the people involved and details that would reveal their identities have been changed.

Finally, this is my experience, my story, which is informed by my age, race, gender, and social class. I am white, female, gender queer, and from an elite, land-owning family. I am an elder, a member of Generation X, who was working with Millennials, but serving people of all ages, races, abilities, and sexual/generation identities. I earned a doctorate in History and Gender Studies in 2010 and have been teaching, writing, and traveling since then. I took the job at A Rose! to learn more about cannabis, and also to replace income sources lost during COVID, as my part-time professor and yoga teaching gigs were not paying the bills. As a single person, I’m often overwhelmed by the amount of invisible wage-work-support labor at home. As one of the only parents on staff, I sometimes felt alone in my struggles with my young adult daughter, her boyfriend, and the young adult roommate I needed to keep the lights on and the Mortgage mostly on time.

In the lean months of January and February of both 2022 and 2023 between semesters when the university check skips a month, I found it hard to buy groceries and dog and cat food. During my 18 months at A Rose! I lost 15 pounds, going from a healthy 135 to 120. My skin is so dry that it cracks from the low humidity required for the cannabis to stay fresh and the constant methane gas leaking from the ancient sewers below. Where the uniform t-shirt rubs from the repetitive movements over the POS system and the counting of the rich man’s money, sores form, stress creates back acne sores that won’t heal, and my feet are swollen from standing.

My immunity was at its lowest in February 2022 and I finally caught the COVID. While sicker than I’d been in a very long time, the basement drain was backed up, the fence separating my yard and my animals from my dick of a neighbor fell in a wind storm, and my youngest kid moves back in with her boyfriend, as they also had the virus. In mid-February, I’m one of three sickies, one well roommate, one toilet, no laundry. The dick next door calls the city and within two days of the fence falling I get a letter from the lawn police threatening citation if the fence isn’t fixed. Then the cat dies after a huge vet bill almost saves him.

Things got as low as they could go in the coldest month of the year in Cleveland.

******************

I understand the lies of the American dream even better from my time at A Rose!, namely because I mostly liked the work, mostly enjoyed our patients, mostly liked my co-workers, but doing an excellent job, showing up every day no matter what was going on at home or with your own body wasn’t good enough to earn a livable wage.

This is true even for me, the highly educated white GenXer with a house in Cleveland Heights, the one with two other jobs, with a family who can help if things get too dire. Unlike Ehrenreich, I entered the role of PCS as myself, I went home to my modest, but comfort house with a yard, most of the time there was enough food, my utilities were never shut off, I still have a nice car that I could count on getting me to and from work. I spoke, wrote, and interacted with colleagues, managers, and patients as my full professional self. When something seemed wrong, I went to management and when Laura was gone, that meant to the district manager and above. I used the tools the white man likes best–email and Teams chat, the latter being an important tool for holding “corporate” accountable. As an elder and a teacher/professor, I gave praise to management when something they did worked well. All of these factors made me an asset and a threat to the company.

Some of the psychological harm and pain I felt was based on ignorance around sex/gender, race, and age from managers, colleagues, and patients. A gender studies professor, I often found myself asking: “Is this an instance where I would adamantly tell a student to act–to hold abusers and misogynists accountable?” When the question started coming up on a daily basis, by March of 2023, I knew I had to leave.

I knew that I would not be safe holding them accountable while I was still working there.

In my people’s European histories he eradicated the knowledge by killing the source: the witches, the healers, the midwives… the peasants wanting to live on their own terms in the Black Forest of southeast Germany, for instance, my ancestors. It was genocide. They destroyed bodies. Did harm to themselves, as the earliest instance of the genocide begins in 1342 in those woods, just five years before the Plague hits Europe. The midwives had remedies for vermin, including keeping cats, which kept rats and mice populations under control. The European white man terrorized peasants first by burning their cats, resulting in an increase in rats, and, subsequently the spread of a plague spread by fleas on rats.[1]

Instant karma.

At A Rose! and in the white man’s late capitalist-apocalyptic eleventh-hour plan to make bags and bags of cash on the cannabis plant, our bodies, like all bodies of wage laborers in all of labor history, were blatantly exploited.

Refusing to see the reality of the workers under your care is a form of abuse.

*****************

I’m getting ahead of myself in the narrative of a budtender.

Back to the party, where things are idyllic and the females hold court, even Mike’s spouse, Alicia, who does a shot single malt scotch with us, as we pass Laura’s PuffCoPlus, which is loaded with Durban Poison badder. Finally, Ramona pulls up a chair with a bowl full of some kind of Cool Whip, Jello, and marshmallow concoction. I lean toward her, eyeing the multicolored gelatin; “Ramona,” I whisper, jokingly, “When’s the last time you’ve seen a Jello salad?!”

We laugh; “I know, right?” She says her middle-class and rising Shaker Heights mother was single, too. Through Ramona, I feel a parent-kinship with this woman I’ve never met. Somehow I know that as bare as cupboards got, she wasn’t going to put anything as food-coloring-rich Jello and chemical-laden Cool Whip on her table.

For a moment, we sat around Mike and Alicia’s table like a multicultural salad of people united in our work with and love of the Plant. Laura, Karen, Mya, Ramona, and me—we didn’t know each other really, we were work friends, but the beauty of Laura’s leadership was that she assembled a team of people whose skills overlapped and complemented one another.

The resilience and brilliance of her team would be necessary under Otis and Brydon, and amid the queer-feminist backlash of 2023.

[1]Jason Ward, “Did Pope Gregory IX’s Hatred of Cats Lead to the Black Death,” https://medium.com/illumination-curated/did-pope-gregory-ixs-hatred-of-cats-lead-to-the-black-death-327d163adfb2 (accessed November 24, 2023). The question of whether the cat slaughters contributed to or led to the Black Death likely remain open for academic and pop culture historians, alike, as we have Gregory’s June 1233 papal bull, Vox in Rama that linked cats to Satanism and witchcraft. There are records indicating that throughout most of the medieval period, cats had a horrendous time and were tortured and culled in huge numbers, and that there were even at annual festivals where cats were killed and strung up. The courts and church would not have kept records of the number of felines slaughtered, as they would’ve been inclined to do when they tortured and executed the peasants and witches over the next 500 or so years.

Chapter 2. Enter: Production, Industry, and Change-chan-chains

In almost every job I’ve held since earning my degrees I can usually find strong reasons to stay at a job I’ve chosen, even when I’m miserable because of the office politics or the kind of tasks that I take on or am assigned are less interesting than I’d hoped, or way more work than is possible in the time frame allotted. We all do it, us workers, whether we’re teaching at a university, repairing electrical lines and circuits, or waiting on tables–we find what makes work bearable because looking for new work is also work. Plus, the new job, we all remember, always looks good from outside, but once you get in there, learn the basics of what you are supposed to be doing, you learn that workplaces are a lot of families. It takes time to learn who among your new family gossipers, back-stabbers, pranksters, are or–more importantly, who among them are collaborators, leaders, and innovators.

At A Rose! However, things are different from any other job I’ve held. For me personally, as a thinker, writer, teacher, artist, most of my previous and current work happens in my brain and is transferred onto a computer and disseminated (or not) online or in print, or comes out of my mouth in the classroom. The heavy lifting comes with staying up late to plow through “A Battle or A Conversation: Imagining Africa in its Diaspora in Beyoncé’s ‘Black is King’ and ‘Lemonade’,” in time for the next assignment to up for my online sections of Introduction to Women’s and Gender Studies 151, or in taking a writing assignment that is due on during finals week, when I’ll also need to skim 20 or more paper drafts and field texts from another 20 who “forgot the paper is due Friday.”

It’s stressful work, for certain, and none of it–the writing, the teaching, the consulting makes much money. In my long work life (I began working at 14, babysitting for one week, then occasionally over the next year and a half until I was old enough to hostess in a popular Italian restaurant in the small town I lived in during high school), I’ve learned that the jobs that have cost me the most in emotional and psychic pain and suffering are the ones that paid the highest. There was physical pain, too. The sitting and slumping that happens after hours on a screen, bound to a chair. However, these pains are massaged away, or can be worked out of a three-day weekend, or an extra paid personal day. And when I held these jobs, I was partnered, so even the household chores were shared, the bills distributed across at least two full time paychecks, while the side gigs and consultant work paid for weekend get-a ways and summer vacations.

Before COVID changed our lives in spring 2020, I had just left a toxic full time teaching job that paid $60,000 a year, and was filling a bit of that lost income with a part time job as a personal trainer for a flight security executive and his team. For $75 an hour, twice a week, I spent an hour with Bob, the CEO, and another hour with his team of gossipy, stiff executives and their dedicated assistant, Doreen, who came every session, keeping my job secure even when the execs were “dismissed from yoga this week” by Bob, who would tell me while huffing and blink- eyed after savasana on at the corner of the corporate gym on the dusty carpet next to the mirrored wall, “The girls are dismissed today, but Dorene will be down to be sure that you get paid,” as if his forcing Dorene to take yoga with on her lunch break so the yoga teacher stays loyal to him was supposed to sit right with me.

Usually before he got the words out, Dorene was walking into the gym, cheerily and smelling of dryer sheets. After six months, I knew her wash cycle well–“I remembered to wash my yoga t-shirt this week,” she would say as she changed in the locker room next to the two double lockers Bob secured for us to store the weights and yoga blocks and blankets.

Most of the time Dorene talked about her dying father and abusive brother, or about her cats, which were terrorizing each other—and subsequently, her, in the condo she lived in 30 miles south, in Medina. We did some poses and she started to really like yoga. At the end of the practice I would give her broad, muscular, and extremely tight shoulders a rub with some lavender oil. This little bit of care is really what made Dorene keep coming. This woman carried the weight of this flight security company’s financials on her back, I felt it. Given this, I had the sense that she only came to yoga on her own terms, despite Bob’s “orders.”

So for two years this was my routine: Tuesday and Thursday with Bob and Dorene between 11 a.m. and 1:30 p.m. (counting for travel and set up time), women’s and genders studies courses–one online, one in-person on Mondays and Wednesdays from 4:30-5:45 p.m., yoga at Abide twice a week for total of two and a half hours. There was the desk time–the lesson planning, grading, researching/writing, but my total hours of having to be somewhere, having to be “on-time” were 10 per week, even with three jobs in the mix. This is a very privileged existence, of course, but within the context of the privilege is a drive to learn more, share more, be curious with others, write with purpose, and build community, it’s required a great deal of hard work and diligence.

All of this hustle still didn’t touch the $60-75K I’d earned in previous years, but the lower income with my teenager at home gave us access to Medicaid and $320 a month in food Benefits. With the two additional classes at Abide Yoga, where I’d been teaching since 2015, and the adjunct teaching at Cleveland State, plus $750 in child support, I was still living well in a home I own, with a car in my name in the driveway, plenty of nice furniture, original artwork, and–most importantly, I was traveling, taking four international trips within the span of three years.

But all of that changed in two days, over March 16-18, 2020, when I was in San Francisco for a panel discussion a friend and also former employee of the girls’ school. We organized a session with students and faculty at Marin Academy on grappling with the “n-word” in schools and communities, reflecting on how the word had hurt us both (she a Black female, me, remember, white) when it broke out in our school on several occasions. We talked about how we healed our friendship. This was the work I was embarking on on–literally, the eve of COVID-19 becoming a reality in the U.S.

If the nonstop flight to San Francisco on Monday was strange for the kind of social interactions occurring in the airport and subsequently on the plane, with parents standing between their children and anyone who as much as opened their mouth to yawn, and elders who had just learned that they were especially at risk for this strange virus policing anyone who as much sneezed with looks of fear and loathing, the trip home was something out of a sci-fi movie–I’m thinking here of 12 Monkeys, which, if memory serves me, depicts a failed attempt to contain a deadly virus.

By Wednesday, March 18, 2020, only a few of us were on airplanes. On my cross-country flight from the west coast to Cleveland, there were just 25 of us on a Boeing 737. I was seated toward the back, and had rows and rows between the next person. No one was yet masked except for two separate Asian couples, who filed past me at the last call for boarding. Both pairs were in their 20s, all four looked shaken behind their masks, perhaps more fearful of what their ethnicities–real or projected by outsiders, meant since the pandemic began in Wuhan, China. Their anxieties were real; I watched a man several rows ahead of me lift his airplane blanket over his head as the second couple walked by.

The day after I returned, March 19, Bob the CEO called.

“Lyz, are you coming to the office today? I don’t believe this flu shit and I’m making my employees come in. We’re going to need you more than ever, and Allison,” the yoga-teaching friend I brought on to attend to Bob on Saturdays.

“Bob, have they shut down your building?” I ask because I’ve already received the email from Cleveland State that we are going all virtual next week. Thankfully they’ve given us an extra week of spring break to redesign our in-person courses, learn Zoom, and–most importantly, help students get the technology need to stay in the class.

“No, but they closed the gym, so I thought we could either use it at 6 a.m. before anyone gets here, or you could come to the conference room in our offices.”

“Bob, you–your health, is reason enough for Allison and me to take a break from yoga and weight training,” I say, trying not to sound irritated by his selfishness and entitlement, reminding myself of how fragile he is physically. The man is 85, diabetic, has some kind of heart condition that causes his extremities to swell up now and then, and is a hateful son of a bitch.

“I can’t believe that you believe this bullshit. You and Allison are Ph.D.s–how can you fall for this Fauci garbage!?”

Bob hangs up on me. I call Allison to warn her of what is coming. In truth, I’m a little skeptical of COVID, or what I call “SARS” in the early days, perhaps as a way to make light of this new virus, ironic humor is one of my weapons. The historian in me remembers that SARS stayed mostly contained in China, the global citizen in me knows that it’s a different world, but I will continue with “SARS” at least until the end of March 2020. Allison is a medical anthropologist and this makes her unable to take my more emotionally distant approach.

“As much as I can’t stand him sometimes,” I say, “I will not be the one to kill him.”

“Absolutely,” then, “That man has so much going on health wise a cold might take him down. And his attitude of defiance on this–” Allison growls.

About ten minutes after we hang up she texts: “Bob called, swore at me when I said ‘No’ to yoga, I hung up on *him*-thanks for the warning,” with some laugh emoji, punctuated by the one emoji with the eye roll and the straight line mouth.

We never talked to him again and in less than a week, my already modified budget dropped $1,200 a month. I held my last in-person yoga class at Abide on Saturday, March 21. The $350 a month from there dropped to $100 during COVID.

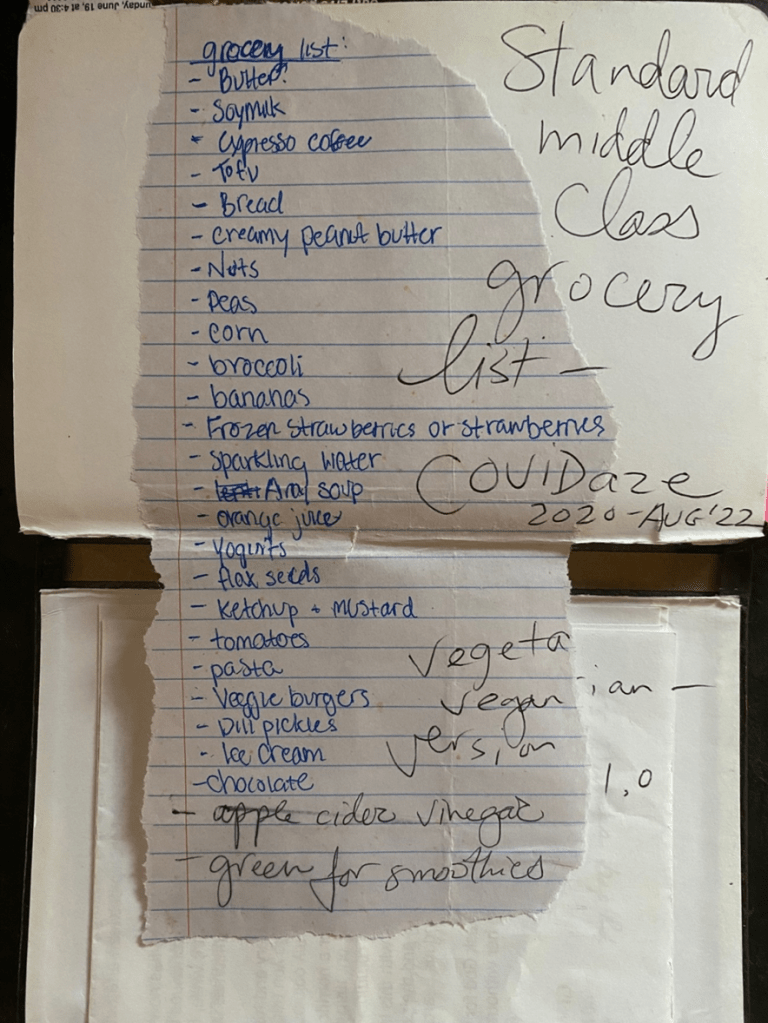

I’d been looking for work and took a consultant gig for an Akron art nonprofit. It paid $5,000 and kept me busy for five months at the beginning of 2021, but by July of that year I wasn’t making ends meet so I started applying for work–even hourly work to ensure a steadier stream of income than teaching and yoga were providing. If I was going to work for a wage, I decided that I should learn more about one of my hobbies, and growing cannabis and all things was becoming more and more central to my summer budget, which in the COVIDaze, was leaner than ever.

At my homestead in the Heights I raised hens and built soil for growing year-round. The cannabis I grew was potent because my soil was rich and alive. In November 2021 I decided to apply for a job at A Rose!, where I go regularly for my medical cannabis. It’s a diverse crowd of PCSs, including Dante, the handsome and charismatic light-skinned Black man with dreads, who sold the first jar of cannabis legally in downtown Cleveland in early 2019 when the store was finally permitted by the state to open. Moy had been there since the beginning, too, and so I let their gender-queer-POC presence vouch for the place. As a patient I was always happy to see Moy in the security booth.

They always wear a medium-wide brimmed black felt hat, and for a time the hat included a large safety pin, pointed upward, at the back of the brim. On the day I noticed it, after Moy buzzes me into the sewage-smelling utterly utilitarian vestibule, the only thing that isn’t white and dirty is the wooden sign that, now that I’m inside, says, “Closed,” I bashfully ask, “Moy, will you tell me about the pin on your hat?”

They are busy pulling my Ohio medical marijuana account up and have the razor sharp focus of someone who’s too brilliant to be able to focus on such ridiculous matters as the state and its system for keeping track of our “days,” or units of marijuana.

“Uh, you have 43 days and a pre-order–come on back…”

I think Moy ignored me, but they rolled the overstuffed office chair that I would eventually sit on in security to the opened door between “patient waiting” and the booth, and said, “Yeah, the hat, err, the pin… I’m not sure why I did it, but I think it connects me to the sky. You know, the heavens, the universe.”

“Thanks for telling me that, Moy. I believe it,” I say.

Moy smiles a smile that I get to know very well in the months that would come after the conversation about the safety pin on their hat. It’s the kind that is wide and their cheeks turn upward with the corners of their mouth. Their nose is long-ish and points slightly down as they smile. Their eyes, brown and wide, and–on their hardest days because for a while they lived with their partner above a raging homophobe who also prided himself to be a gangster-baller, and he would stomp around, blast music, play football with his kids making sleep for days on end impossible–sometimes circled in charcoal-dark circles, were always kind, usually curious, steadily intense.

I decided to apply at A Rose! because Moy is there. I know that they are queer, I know that they are an artist and a dreamer like me. I also like Dante and have just started to know the elder people that the manager–Laura, remember, recently hired. Karen is, like me, in her 50s. She’s short and wide, a former hairdresser and makeup artist-sales-person at MAC, she chats me up about nail polish while she rings up my order of Orange 43 flower and, she says as she packs me up, “Your Kush Mints for rest. Good choice, I like that one, it helped me heal my uterus.”

These are not the kind of conversations you have at the MAC counter, or at Whole Foods with your perky cashier, nor even with your server at the Thai restaurant where you regularly dine. But in the world of medical cannabis, the plant is the prescription.

“Well, I hope it relaxes the pain in my upper back,” I say, trying to avoid a longer conversation about Karen’s womb, plus, I’m on my way to class and I have to find parking.

“Take care and be safe,” she tells me.

“You, too!” and I’m already through the first big mental door toward the one at the vestibule. Moy is with another patient, but they look up and send a distracted wave my way.

**********

The next time I see Moy I’m confusedly fumbling with my ID in the vestibule, but this time it’s so they can make a copy and give me my visitor’s badge, which I’ll use for the first part of the morning while we wait for my official badge to arrive via FedEx. Moy hands me the visitor’s badge, which is really nothing more than laminated blue cardstock with “Rise Cleveland Visitor, #004” printed on it. I put it on and follow them to the sales floor, which I’ve seen multiple times from the patient side of the counter, but Moy beeps me in and leaves me with Jody, the shift supervisor who’s supposed to train me because Laura, the store manager, was supposed to, but she has COVID.

Mind you, this is the week of December 12, 2021, full-on COVIDaze. The holiday season is in full swing, so the sales floor is decorated in tiny little sweaters that say “Have an Incredible Holiday Season” on them, which references the Arise house brand edibles. I can’t get the image of someone trying to stuff their tiny miniature poodle Fifi into one of them on Christmas morning. Then, like now, everything in this utilitarian medical-retail establishment feels slightly “off” aesthetically. Case in point: hanging these tiny dog sweaters on the Plexiglas divider “protecting” us and the patients from spreading COVID.

The place is understaffed, so Jody waves me over to register 3 where she’s just finishing up with a patient I would get to know well over my 18 months at A Rose! “John, this is Lyz she’s training today–by next week she’ll be taking care of you.”

John is one of the most affable men I’ve ever met. He’s a limo driver–his specialty is getting the pilots to CLE Hopkins on time, which is stressful, but fun for him, it seems. “Welcome–Lyz! I’ll see you tomorrow!”

I was surprised that he would be back tomorrow already, and Jody seemed to read my mind: “Every patient is allowed the equivalent of a 2.83 gram amount of flower, and some patients use that or take advantage of it. John is one,” she tells me.

With no competition nearby and A Rose!’s status as a national corporation, they charge what the market will bear, which, in December 2021 was $38-$45 for 2.83 grams of flower, and most customers purchased cannabis in flower form, each daily allowance packaged in glass or plastic jars, with the occasional BPA-free plastic envelopes. People purchase a lot of edibles, too, even as they cost an exorbitant amount of money in medical-cannabis-only Ohio, while recreational cannabis is available just two hours west, in Michigan. Likewise, vapes are abundant and cheap in Michigan, but the oil used and how it’s processed is what makes vaping cannabis medicinal. Cheap cannabis sludge processed with butane, ethanol, and/or propane into disposable vapes and cartridges gives the body as many harmful toxins as medicinal Benefits. Ohio patients who regularly traveled to Michigan to save money and get potentially higher THC levels in their processed vapes and edibles were some of our most obnoxious and annoying customers.

Even in 2023, as competition from medical dispensaries increased and prices at Arise went down to keep in step with what seemed like a weekly addition to the array of medical dispensaries popping up in the ten mile radius of downtown, outraged Michigan shoppers laughed rudely in our faces. One woman, who enjoyed having her younger, handsome cousin-caregiver at her side as she roasted me for our prices, seemed to shop for the sport of it, taking down the budtenders for the cost, amount, “quality”–which, to most, meant “the best” or highest THC.

She is well dressed, with an authentic Gucci bag, thick, heavy Prada framed glasses, a smart matte lip, a good wig that has her long, wide curls swing from side to side as she saunters up to “reg 1,” where I welcome her: “Hey you two, come on up–I see you are a new patient, Patricia. May I see your photo ID and your Ohio Medical Marijuana card one more time, please?”

Patricia fumbles for both, like everyone does, as the cousin flips his ID my way, as a seasoned caregiver would, “Here you go,” he says as I nod and he puts it away. Patricia is still scrolling through her pictures to find the screenshot of her ID, and her long nails tap nervously next to her driver’s license. “Ah! Ohio,” she starts, “in Michigan I woulda been in and out of here with a half ounce at 40%.”

She lifts the license and simultaneously shoves her greasy phone screen too close to my face. I ignore it, knowing that Moy already checked and double-checked Patricia and caregiver Daryl’s credentials, so even though I can’t see either card I say, “Ok, 40 days of supply available through April 30, how can I help you today?”

“I want an ounce of the best flower you have and I only have $150, what can you do for me?”

It’s been a long day already, with the sales on the cheap brand of house flower selling fast. This brand fits her budget, but I already know she’s going to turn her nose up at the THC of 22.5%. I decide to cut to the chase with Patricia, who’s talking to Daryl between comments to me, about how wonderful it is to be able to smell the bud in jars like they do in Michigan.

“Patricia, the flower that gets closest to your request–based on your need for a high percentage of THC and budget of $150, is this Layer Cake–”

“What’s the THC?”

“This one is at 30.1%,” I tell her, knowing that whatever number I gave it would be met with a scoff.

“Daryl,” she talks to him, telling him what she wants to tell me, but she can pretend she’s not being rude and hurtful to the human being who can’t tell her to go fuck herself, “They want me to pay $150 for a HALF ounce of weed at 30?!”

Daryl laughs uncomfortably, looking at me sympathetically, as if to say, “Don’t take it personally, she’s cruel to everyone, especially me…” I shrug. If I wasn’t tired, if I thought it would change her mind, if I hadn’t already had to defend some state of Ohio bullshit that truly did not make sense–why a typical eighth ounce–or 3.5 grams doesn’t exist. Rather, the State decided that a majority of patients would get the equivalent of 2.83 grams for one day. They, and the few corporations who began selling medical cannabis in greater Cleveland in 2018, decided that this unit of medicine would also cost patients roughly $38-45. A two-day, or 5.66 grams supply is the next size available, and it cost, in those earliest days of the program, anywhere from $85-89.

While most people didn’t use their 2.83 jar in a day–in my case, for instance, that lasted a week if I bought two jars, sativa for day, indica for night, which even then was beyond what my budget could sometimes afford. Rightfully so, patients were often confused and pissed about the State’s control and oversight, but reminding them day-in-day-out and hearing their criticisms and being confronted with their vitriol over it sometimes felt abusive. So when Patricia finished her diatribe over the “Ohio program” by laughing it snidely out of her mouth toward Daryl, I pushed her driver’s license back toward her and said, “I’m sorry then, Patricia, it appears that we cannot help you today.”

This pissed her off even more. “Do you believe this bitch, Daryl? This place?” Patricia huffed loudly and turned on her too high for balance heels, stumbling just enough to drop the driver’s license to the floor. Daryl is looking down, having just retrieved the license and using his downward glance as an excuse to avoid my eyes.

“I should sue!” Patricia is now embarrassed for tripping over herself and that’s also my fault. I give her “dead eyes,” again, a weapon I’ve had to employ at almost every job across my varied career. It’s a wall that I create that is particularly affective because I am normally and/or at first very kind and charming. When the shutdown happens with Patricia and, by proxy Daryl, I watch as she looks away from me, toward the exit door, where he’s holding it open.

Before she exits I catch her profile and I see just a short glimpse of shame. This is common. When you don’t reflect what people put out, when you give them nothing, they are left just with themselves. Patricia also looks a little shook, like the stumble was a correction from her God.

Patricia’s little uppity outburst were common, but these kinds of slights were not the worst we would bear the brunt of. When you live in a city of four seasons you come to expect that people’s personalities shift according to the sun. It’s not as simple as “When the sun shines we are happy,” or “Joe’s pissed because he had to dig himself out of six inches of snow before leaving the house today.” Yes, of course, seasonal depression is real. Of course, people like blue skies better than grey, temperate more than frigid weather. But in CLE, like everything else, the psychology is complicated.

My anecdotal research is that in the CLE, regular folks like sports. They are die-hard fans. I’ve known this my entire life, admit to many afternoons falling asleep as a teenager under the Cleveland Plain Dealer or The Akron Beacon Journal, both of which were delivered to the house on Sundays, with the Cleveland Browns announcers’ voices droning and the faint verbal energy and chatter of excited fans in the background. But when I went to grad school, I left the television and the sports behind, except to critique them using my latest theories gleaned from the top-10 state school two hours south. It was easy to avoid sports as an adult and it wasn’t until I started working three blocks from the baseball field and adjacent basketball arena that I would learn just how much these games made of men chasing balls of different shapes and sizes affect people’s moods.

On Sundays, in the winter and fall, men in sweats would start to arrive for their afternoon cannabis at 11:00 a.m. As I waited with Kevin, one of my favorites of the sports-Sundays crowd, I’m asking my usual of him: “Ok, so who are we rooting for this week?” because he knows that I count on him to give me the pick and a few stats to share with the sports-lovers who come in closer to game-time. They are nervous and uncomfortable with how long it’s taking them to get their cannabis (interestingly, these types rarely change their behavior to make themselves less anxious about missing the kick off, the coin flip, the cup grab and spitting or chalk spreading and cup grabbing that ensues at the beginning of the game, they just get mad at me for not making things go faster).

“I’m picking the Giants, but only because I have money on the game. Otherwise, I don’t care…”

Even he has his mansplaining managing my job moments, though, “Hey–is that my Garlic Cookies?” he points to the clear package of dry bud, which he will complain about but take home every time regardless. I pause, because of course I heard the mail slot that Manny’s placed it in open and shut, but was going to let him finish his sentence.

“Uh, yeah,” I stand firm because these men will push you hard if you don’t play hard with them on occasion, “Anything else I should know about the Giants?” and I turn on my heels to get his package as he rambles on about the center being hurt or some guard having a concussion.

“Yeah, yeah, it’s fine,” he waves his 36% THC garlic cookies away and we both smell the funkiness of it through the sealed bag, “Dry as usual,” he starts to grab the bag before I finish stapling it, per the state’s rule. “Kevvvinnn!”

“Oh right, right–my bad,” he says, but still grabs and runs.

It’s not so much what the anxiety-ridden Sunday sports fans said, it was how they acted. Entitled and like human existence was in the balance if their asses were in their gross man caves, asses in grooves of their reclining faux-leather fart chairs at or by 12:59 p.m., BBQ chicken wing in one hand, stanky garlic cookies blunt in the other.

You are in the way of them getting what they want on their exact time schedule, regardless of what is going on in the world, or with other people who might also need to pick up their cannabis on Sundays at 12:00 noon, and more often, because they have only one hour on Sundays at noon between job 2 and job 3 to pick up their medical marijuana.

Near the end of my time at A Rose!, my Sundays were spent in the security booth, which was fashioned a bit like the vestibule in a methadone clinic, I imagine. It’s in our downtown location where the paradox of medicine/commodity with the state of Ohio’s regulations and what each individual dispensary negotiated with them to open based on location, type of structure, patient/customer demographics, and, in the case of Arise, connected as it is to a major national corporation, whatever it took to open in the Ohio medical market.

Here’s where the Patient Care Specialist, be they waiting on patients on the sales floor, or giving them access to the space in the security booth, takes the heat when the state rules don’t allow for a pleasant and easy retail transaction. Add the truth that corporations suck and in a “novel business market” like cannabis (medical or recreational) they don’t want to spend money on new equipment or better wages or even a reception desk that wasn’t literally falling apart across from waiting patient-customers’ eyes in the waiting area.

So when something like the scanner, which was required to work to let patients in the door, didn’t work properly, we looked like we were incompetent. In all of the dispensaries I’ve visited in the state with the exception of A Rose! patients’ medical marijuana cards are scanned, then there’s a scanner for the state of Ohio driver’s license, which links to the ID number and auto fills in the OARRS Medical Marijuana System.

Not A Rose!

There, through scratched, finger-printed, almost translucent, non-bullet-proof plexi, patients hold their ID so that we can check to make sure it’s still valid, and then, through the plexi barrier, we read their driver’s license or state ID number and type it in to the second available field in OARRS, where we go to determine who many “days” are left in a patient’s prescription. Generally, each medical patient in Ohio gets eight periods of 45 days and one period of 46 days, which essentially adds up to roughly 45.5 ounces of flower over the period of their recommendation (406 days). None of it makes sense, even now after working there almost a year and a half, I don’t think I could explain the rationale for these numbers, and for most patients, these were more than enough days.

But in the days-daze since I left A Rose!, I’ve come to understand that the patients who were aggressive because they ran out of days (meaning they used their entire 45-day supply before the next 45-day supply date reset), were addicts. Not in the sense that they were addicted to cannabis, but in the sense that they had been addicted to something previously and the only thing that kept them from creeping back to their drug of choice, be it cocaine, heroin, or oxy, was the strongest THC in the house, as much as possible, every day, 2.83 grams.

When they called to find out that they were “out of days” they would often swear at you, as if you made the rules, or smoked all of their cannabis behind their backs. Even seasoned patients, those who you saw and laughed with nearly every day could become toxic.

On one of the darkest days of February 2022, amid the snowiest winter the CLE has had in years, I’m on “intake,” a position I fondly refer to as “A Rose! Secretary,” and I make it as ironically GenX fun as possible, sauntering through order fulfillment on my way downstairs to the breakroom, I’d ask the manager or pharmacist: “A Rose! Secretary at your service–does anyone need a coffee?”

The answer–always, “No,” as they believe this to be a trick of the feminist gender studies professor, which it is, but I really would get them coffee. Once, Laura the manager asked, “Are you serious about this, does this mean you like or don’t like the intake role?”

I laugh, the millennials do not get me and I am alone in this, the eldest among us, “I love it!,” I say as I slip through the door to the basement.

On this particular February day, I have just settled back from my first coffee run of the day. I settle into my chair, which I’ve switched from the cushy one on a wheel that hurts my lower back to one of the perfunctory IKEA-white ones that the patients sit on in the waiting room.

The phone rings and I pick it up, this act of communication rarely occurs at A Rose! Now, Moy recently told me.

“Good morning, A Rose! Cleveland, how can I help you?”

“Ah, ah, I’m calling to see if you have that Wingsuit in the half ounce at 34%,” the masculine voice asks, but there’s no question mark at the end of his sentence.

“We do have that in stock today,” I tell the person who seems like a man, then: “If you want to make an order, I need to check your recommendation, what is your name, date of birth, and zip code?” I ask with the proper query-inflection.

The man gives me his information, per HIPAA, everything checks out as far as his date of birth and zip code, but Ohio’s system for tracking Timmy’s days kicks me off before I can check if he has the five days left on his recommendation needed for the half ounce.

Usually people who already know that they are out of days are the most aggressive. Timmy is one such patient.

“Hold on, Timmy,” I say, trying to keep him engaged in the bullshit process in front of me while he waits in line. I log out and in again as is sometimes required in the HIPPA-forward OARRS system.

NO REC; do not dispense. It’s February 15 and Timmy’s days ran out on the 13th. It’s bad news, and I know Timmy is going to take his addiction-disappointment out on me.

“Timmy, it looks like your recommendation does refill until the 20th of this month,” I say blandly. “You’ll have to wait until then to place an your order for–”

His energy is on ten: “That is not right because my card says the recommendation expires on February 28, 2022 and today is only…”

I cut him off, because this happens every day, remember.

“Timmy, I’m sorry, but that is for the registration card, the doctor’s recommendation ends on the 25th of the month, and you’ve used all of your days for this month and for the year…” the news is worse than even I realize and Timmy is pissed and confused.

Imagine if CVS or Duane Reade required you to pay $50 to get your prescription filled, but your prescription runs out before your membership card. So you’ve paid the $50 for the year, but your doctor’s appointment is in early February and your membership ends on February 28. Both the doctor’s appointment (not covered by insurance, unlike what might be the case at the drugstore) and the membership card must be paid and in order, even though they expire at different times. Oh, and the doctor’s appointment is not with your regular provider. It’s with a specialist who charges anywhere from $99 to $250 to “approve” you for the medical cannabis card.