Lyz Bly/DRB, Ph.D.

“It is time to recognize that the major effort of our country until today…is not to change a situation, but to seem to have done it.” – James Baldwin, “The Artist’s Struggle for Integrity,” 1963[1]

“If we compare the natural duties of a father with those of a king, we find them to be all one, with no difference at all except in their latitude and extent. — Robert Filmer, Patriarcha, or, The Natural Power of Kings, 1680 [2]

In 2006, while in the heat of digesting hundreds of years of American gender/women’s history, European imperialism and racism, as well as further analyzing my academic loves—philosophy and critical theory, I sat in the Case Western Reserve University library trying to distill everything I was reading into an active sentence. There’s a reason that only 1.2% of Americans have Ph.D.s. It’s not necessarily that we are smarter, it’s–I feel, that we have a higher threshold for pain and torture.

After six months of living–literally, underneath these books for 12 to 18 hours a day, I needed a goal, one grounded in the history I was learning. “If there are so few of us,” I thought in between posting post-it notes in books on labor history, gender theory, and the entirety of American History since the Pre-Columbian Period, “I need to come out of this experience with a phrase that I can eventually put my activism behind.”

Out of nowhere it came, just a week shy of my comprehensive exam defense:

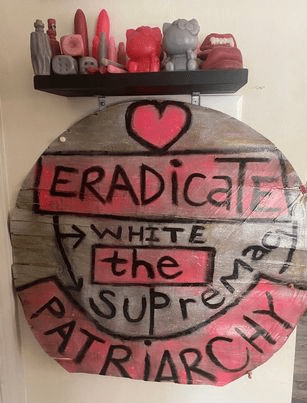

ERADICATE the PATRIARCHY.

“It’s a disease, this ideological way of life,” I surmised, “We need to root it out of our brains, our actions, our bodies.”

I passed the comprehensive exams in April of that year and, in as I recovered from the emotional and intellectual hazing involved in the process, I decided to celebrate by designing a sticker donning the phrase. I ordered 500 in the 2 x 4″ size, and sprung for glossy, waterproof finish, surmising that the black and white would make the words “pop.”

It was a simple design, echoing my succinct slogan the point. At 3 x 4 inches in size, a sticker could hide under your palm, non-stick paper removed, ready to post on any offending street sign, car bumper, or public restroom.

ABOVE: ERADICATE the PATRIARCHY (To Banksy, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, August 2019)

Bush 2 was in office in ’06 and fewer people were carrying guns, so the stickers functioned first as an agit-prop[3] project. I handed them out to friends and students and we would cover Bush-Cheney 2004 or anti-choice bumper stickers with them.

Once, my friend Jill and I covered the entire door of the Cigar-Cigar Shop on Lorain Avenue with the black and white laminate (they created a particularly sexist billboard, or some such nonsense). The next morning, the owner found 50 or so ERADICATE the PATRIARCHY stickers, placed pell-mell, melting onto the hot glass door in the summer sun. The next time we saw, Eric, the goth doorman at the nightclub next door, he told us that the owner of Cigar-Cigar came by asking if he saw any “teenagers or college students putting feminazi messages” on their door. Eric, knowing it was us, said—truthfully, “No, I saw no teens or young adults putting stickers on Cigar-Cigar’s door last night.”

In this phase of the agit-prop sticker project, they were to be anonymous tools of dissent. ERADICATE the PATRIARHY held sexists and misogynists accountable—giving them a chore to do (one that often required a trip to the hardware store for a spray bottle of goo-gone), or leaving them embarrassed to have such a message on their precious business or automobile, as sometimes the stickers were not discovered right away.

Once, to send a message to my brother, I pasted a sticker on his bumper at a family function. On the drive home, unaware of the feminism on the bumper of his prized Lexis, he stopped the Costco in his white conservative suburb. As he loaded five cases of bottled water into the back of the Lexus, he saw the sticker and removed it. When he got home, he found a scratch. Someone keyed his car over “his” bumper sticker.

“NOT funny, Lyz. My car got keyed–and it’s a huge scratch!” he texted.

“Welcome to our world,” I reply blandly, without apology. This was in 2018, after all, and he and most male people I knew were behaving badly, wittingly capitalizing on the misogynist order of the day.

It was in 2008 when a student showed up to class with ERADICATE the PATRIARCHY on her water bottle.

I gasped, “Melanie, the stickers are like tiny weapons. And sometimes they go on cars. If it’s on your bottle, it could be recognized by a Bush supporting misogynist, you might be connected with mildly subversive acts.” She waves me off and I remember: “Ok. Agit-prop is supposed to take a life of its own.”

Soon I began seeing them on more water bottles, laptops, and as carefully placed bumper stickers on cars. The message was clear and the sticker looks good. I gave in and started handing them out as “décor with a clear feminist message and activist charge.”

There were several print runs and I began leaving them as sticker bombs around the world. In 2019, before COVID took my traveling agency, I pasted them in Amsterdam, over a Banksy (see above). Later that summer, while in Warsaw, I pasted five over the disturbingly ubiquitous neo-Nazi messages and swastikas that were both randomly and carefully sprayed on walls, over advertisements, and on the sides of trains. In 2017, ERADICATE the PATRIARCHY was left lingering amid French graffiti at Montmarte in the 18th Arrondissement. I hand them out to people I meet through my travels. Once, I saw my friend Mieke from Amsterdam on a YouTube interview about Indonesian identity in the “post-colonial” Netherlands. The sticker was pinned on to her right side breast pocket.

ERADICATE the PATRIARCHY was my central goal as an activist, and my dissertation, published in 2009, was a look at the invention of a third wave of what I called “GenX Feminism.” I argue that those of us born between 1960 and 1980 were shaped by images in popular culture, the subjects of library books, and school textbooks, colonized our minds into believing feminism was everywhere at work for us, moreover, that racism was also being eradicated. Consider PBS’s Sesame Street and The Electric Company (TEC), which began airing in 1968 and 1971, and shown ubiquitously in preschools and elementary schools, including, in the case of the latter, in my third grade classroom. Mrs. Barber, my Wait Elementary School reading teacher, could have Wednesdays free to grade as Easy Reader (played by Morgan Freedman) taught us reading basics in a visual and entertaining way.

ABOVE: The diverse cast of The Electric Company, with Morgan Freeman, who played “Easy Reader” to the far right (https://www.npr.org/2021/10/25/1048365940/50-years-ago-the-electric-company-used-comedy-to-boost-kids-reading-skills, accessed July 29, 2023). Here and in the skits the actors performed the white man was frequently the minority. Often, he was depicted as the butt of jokes, or as an crotchety outsider, through characters such as “J Arthur Crank,” played by Jim Boyd (not pictured).

ABOVE: Page 258 of a social sciences textbook for middle school students of the early 1970s. (From the image bank/collection of the author.)

In school textbooks, we saw images of Latina “sanitation workers” (not garbage men, as they are still often called today) and Filipino/a social workers, while African-American men were depicted at the front of the classroom, or as adult astronauts, doctors, and x-ray technicians. As a white kid living in a predominantly white, affluent suburb 30 miles southeast of Cleveland, I had no context for this diversity in reality. Still, they were teaching us this in school. “It must be true, it’s in the book,” my child-brain thought.[3]

ABOVE: ERADICATE the PATRIARCHY amid Barbie clothes from the 1970s and 80s, including some hand-stitched pieces; homemade doll clothes were common at my house, as my mother had the time, skills, and equipment to whip up new outfits.

Even before her image and evolving meaning came to movie theaters, Barbie’s image(s), her “every girl” mentality and presentation, her impetus for consumption were highlighted on television. In the 1970s, network television and its Saturday morning sponsors took the opportunity to capitalize on our sugar laden breakfast brains, filling them with pink, shiny, sparkly flashes of Barbie doing fabulous things. Mattel commercials showed us the possibilities of Barbie’s ever-expanding wardrobe, of course, but her beauty and fashion also came with cars, campers, airplane, pets, careers. As a white, elite (albeit queer) kid, the wardrobe echoed my own, my mother’s, and my brother’s supply of clothes, which, like my Barbie’s clothes, were a mix of store-bought and handmade.

My Barbies were all white. The “diversity” was in hair color alone. Even brown-haired Barbie (I’ve long forgotten her name), had white skin and pale blue eyes. I had the camper, the car, one of the dream houses, and one of those fold-up wardrobes, likely from the late 1960s, passed down from my cousin Laura.

Of course we knew of the black and brown Barbies, as they, too, were widely advertised on television, namely on Saturday mornings, when the diversity of Barbies was interspersed with the power of characters like Thelma, the bookish side-kick on Scooby-Doo, or Wonder Woman on the live action series (played by Lynda Carter).

James Baldwin had already identified the problem with representation and visibility in “The Artist’s Struggle for Integrity,” in which he says that it seems like the effort in the U.S. is not really to change things (around racism), but to make it seem to have changed.[4]

This—the “make things seem to have changed” phenomenon is an underlying impetus in Barbie, the movie. Indeed, Stereotypical Barbie, played flawlessly by Margo Robbie, is living the dream of middle-class privilege and crass consumerism in her bubble that is Barbieland. This part of the film is reminiscent of Charlotte Perkins-Gilman’s 1919 utopian story, Herland, where three men from the patriarchal world” stumble across an efficiently-running, stunningly-built city of women. Unlike in the contemporary Barbie narrative, however, we see the women’s world through the eyes of the indoctrinated men.

ABOVE: Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s 1919 utopian fiction, HERLAND

Barbie, having never left Barbieland, which is run and centered entirely on women, assumes that her work in the real world was done. Through representation, “she” gave us the idea that we—females, girls, kids, could be anything in the world. I would argue that this is true, and that she is a missing piece in my work on representation, gender, and Generation X, as for me and the girls around me who also played with her, she represented the life we were already living, and would be expected to live, at least until we had to earn our bread in the real world, or decided to take a masculine-dominant course in math or science in college and found ourselves alone, or with one or two other females or people of color. In the latter spaces, it became clear to me that the confidence some of the men students exuded was connected to their gender.

It turns out that most people’s minds have to change along with the images. Barbie Scientist inspired us, but if the middle or high school science teacher believed, as many in the 1980s and 1990s still did—that “girls and women just don’t have the head for STEM fields,” not much could change.[5]

This hits Stereotypical Barbie when she leaves Barbieland and goes to Los Angeles to find the person playing with her—supposedly “her girl,” and it hit me in reality while I worked as a server in the late 1980s during college. While learning feminism during the day in art history, philosophy, and psychology courses, it was assumed that my body was part of the restaurant work I did at night. My Barbie “ass slap” came when I went to table one at the start of my shift and had a working-class man, white, and a “sanitation worker,” as they called them in the textbooks of my youth, grabbed my right butt cheek.

“You’ve got a nice ass.”

ABOVE: The bathroom vanity of my own dreamhouse (find the hidden Barbie items and/or references).

I don’t remember my response. I know that I didn’t hit him. I remember that I told the manager and that he sympathized, but that I finished waiting on the men. Together, they left a dollar, likely a five percent tip.

Without giving too much away, Ken hides in the pink Barbie car in order to “help” her find her “girl.” Both characters go to Los Angeles under the assumption that everything has changed since Barbie came on the toy scene in the 1950s. Indeed, Barbie even heads to a construction site to find “construction worker Barbie” after several cat-calling interactions with men on the street. It’s here where the dream crumbles, at least for Barbie.

As for Ken (spoiler alert!), he quickly adapts to the patriarchy, spouting the word and securing a copy of a library book on men and the patriarchy. Without giving away too much, Ken leaves Barbie in the real world, returns to Barbieland, where he shares the privileges and power of patriarchy. By the time Barbie makes it back, the utopia is destroyed. This may be one of the most comical parts of the film, and hearing “patriarchy” repeated dozens of times by Ryan Gosling, who’s playing a dickbag chauvinist pig, is completely delightful.

There some truth in the scenes of Ken wandering around LA witnessing the backslapping dominant masculine energy. He practices it himself on a white man in an office building. It seems Ken’s taken the patriarchy too far by asking the randomly chosen man for a job with good pay and influence. When told he needs a degree or qualifications, he says, “But, I’m a man!” His new acquaintance says “Well that actually makes it worse.” Ken asks if this makes things harder for men. The reply is something like, “Not really, we just have to be quieter and keep things running the same way.”

Likewise, the imaginary board of Mattel, run by a CEO played by Will Farrell, is made up of entirely men, most of whom are white, aside from two Black men executives, isn’t challenged at all in the film. Farrell’s character spews some paternal niceties (i.e. microaggressions) about “fulfilling girls’ dreams,” “having daughters of his own,” and “all of the board member love women!” They are tongue-in-cheek, but they go unchallenged and this is how Mattel gets with leaving little space for analysis over why Barbie, Stereotypical, at that, would consider leaving Barbieland, a consumerist version of Herland.

ABOVE: Untitled 1 (AGIT-PROP for their apocalyse), 2018

As art, the film is great fun. The creators captured how we play with dolls, some of the characters are stuck in functionally awkward poses, and the historian in me was dazzled by the pop outs of the outfits, including Ken’s mink, which, in the end goes to its original Black Ken owner. Likewise, the queer references throughout felt absolutely celebratory, and is reminiscent of my own play, as a child with my queer neighbor John, whose GI Joe shared the a bed with my best Barbie in the country camper many-a-time. And, recently, my friend John, also a queer artist-writer, and I played with a box of old Barbie clothes outside at a park in Cleveland during COVID.

The inclusion of “Weird Barbie,” also captured a nuanced phenomenon among most GenX queer feminists I know. For punks, it was about recreating Barbie in our own image. In a series unplanned cathartic artworks, I chopped my Barbies’ hair, drew tattoos on them, stuck pins in their heads because I would often miss the tiny earlobes with the pins I took from my mother’s sewing basket.

After college, when I cleared boxes from the family house, the old Barbies (pristine, and punk alike) to promptly delivered them to my rented house and cut all of them to piece on the front lawn. When I was finished destroying them, I broke apart and burned my mother’s “hope chest,” a big cedar box that, in my her day, women were supposed to fill with pots, pans, linens, and towels, for the “hope of marriage,” where consumption of said items would be a constant requirement of the job of “wife” and “mother.”

Barbie’s unrealistic beauty standards, her imperative message: “Work at whatever you want girls, but still, you must consume, consume, consume!” is counter to GenX feminism. Naomi Wolf gave us the language to critique this capitalist imperative in 1991, with The Beauty Myth. In it she argues that beauty standards and norms are much less about presentation or about getting to “beauty.” Rather, the myth creates behaviors—shopping, grooming, primping, exercising, starving oneself, getting surgical procedures to conform to an ever-changing, and never-attainable body and face—or, image.[8]

This, too, is why we destroyed Barbie, as the strong teen Sasha (played by Ariana Greenblatt) character in the film asserts upon meeting her eschewed doll in the school cafeteria in the real world—Barbie, gave us an unattainable bar to reach on the beauty/body front and as human beings simply trying to survive in a patriarchal world. In Wolf’s terms, beauty standards keep us busy buying creams and lotions for our imperfect faces and bodies, compel us to purchase gym memberships, and sitting mindlessly in chairs at the salons and spas.

Barbie was perfection and GenX saw right through that corporate expectation.

There were books written about Barbie in the 1990s; critiquing her was a crash course in the male gaze and patriarchal capitalism. My adult friend John and I recently mused over our multiple copies of Mondo Barbie: An anthology of Fiction and Poetry, published in 1993 by St. Martin’s Press, which had multiple volume Mondo series in the 1990s. “The pages were pink,” I text back, feeling nostalgic.

ABOVE: MONDO Barbie: An anthology of fiction and poetry (New York, NY: St. Martin’s Press, 1993)

Barbie the movie on a hot summer night in July is delightful. Hearing “patriarchy, patriarchy, patriarchy” in the context of a movie theater was like being witness to everyone else finally entering a world I’ve lived for decades, as a female, as a queer, as a member of Generation X. Like my GenX contemporaries, I grew up knowing that representation, image, and now social media are not in any way reflective of the life even the most privileged of us have lived on this planet.

With the slew of men in suits still in charge at Mattel in the Barbie movie, Barbie’s end-of-film decision, still toes the line of patriarchal dominance and misogyny as the standard to which we all still live.

ERADICATE the PATRIARCHY still remains the charge, the order, even with Barbie the movie as a the blockbuster hit of summer 2023.

ABOVE: Untitled 10 (AGIT-PROP for their independence day), 2023

[1] James Baldwin, “The Artist’s Struggle for Integrity,” New York, NY, 1963 (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dU0g5fAA2QY, accessed July 29, 2023.

[2]Filmer, Robert, Patriarcha, or, The Natural Power of Kings (London: Printed for R. Chiswel, W. Hensman, M. Gilliflower, and G. Wells, 1685.ca77d5603c9a504, 4).

[3] Agitation Propaganda or AGIT-PROP is generally defined as “the spreading of strongly political ideas or arguments expressed especially through plays, art, books, etc.” From https://dictionary.cambridge.org/us/dictionary/english/agitprop (accessed July 30, 2023).

[4] Bly, Elizabeth Ann (Lyz; DRB), Generation X and the Invention of a Third Feminist Wave, (Cleveland, OH: Case Western Reserve University, 2010), see chapter 2 (https://etd.ohiolink.edu/apexprod/rws_olink/r/1501/10?clear=10&p10_accession_num=case1259803398, accessed July 30, 2023).

[5] Baldwin.

[6] Bly, 2010, from footnote 5, page 74: A U.S. Department of Education report on trends and education equity for girls and women reports that in 1970 women lagged behind men significantly in all fields of the health and social sciences; by 1974-75 37.3 percent of four-year college students studying the social sciences and history were female. This report also indicates that between 1973 and 1981, fewer women than men were enrolled in four-year colleges upon high school graduation. In 1975, 54.3 percent of undergraduate students were male, compared with 45.7 female, 55.4 percent of graduate students were male and 44.6 were female. In the same year, 20.7 percent of students entering medical fields, law, and theological professions were women, while men encompassed 79.3 percent of those students. See Catherine E. Freeman, National Center for Education Statistics, Trends in Educational Equity of Girls & Women: 2004 (U.S. Department of Education Institute of Education Sciences NCES 2005-016), 78, 69-70. http://nces.ed.gov//pubs2005/2005016.pdf (accessed August 6, 2008).

[7] The week prior to the white elite man’s independence day the supreme court also struck down affirmative action in universities, voted against forgiving Americans’ crippling student loan debt.

[8]Naomi Wolf, The Beauty Myth: How images of beauty are used against women (New York, NY: William Morrow, 1991).

[9] Theodore Adorno, The Culture Industry: Selected Essays on Mass Culture (New York and London: Routledge; 2nd edition, 2001). Adorno uses the metaphor of “toeing the line” in popular culture in this text, originally published in 1963. In my work I cite Theodore Adorno, “Culture Industry Reconsidered,” (New German Critique, 6, Fall 1975, 12-19 [translated by Anson G. Rabinbach], reprinted at http://www.icce.rug.nl/~soundscapes/DATABASES/SWA/Culture_industry_reconsidered.shtml and repaginated as pages 1-17 (accessed June 29, 2008), 1, 15.

Leave a comment